Proctitis is an inflammatory condition affecting the lining of the rectum, the final segment of the large intestine. When the mucosal tissue swells, patients experience urgency, bleeding, and pain. Understanding why the immune system turns on this tiny tube reveals clues for better prevention and therapy.

What Triggers the Inflammatory Cascade?

At its core, proctitis is a response to a perceived threat. The most common culprits fall into four buckets:

- Infectious agents - bacteria like Shigella or viruses such as HSV.

- Radiation exposure - pelvic radiotherapy for prostate or cervical cancer.

- Underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) - ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

- Ischemic injury - reduced blood flow after surgery or vascular disease.

Each trigger sets off a similar biochemical chain, but the initial signal determines the downstream profile of immune mediators.

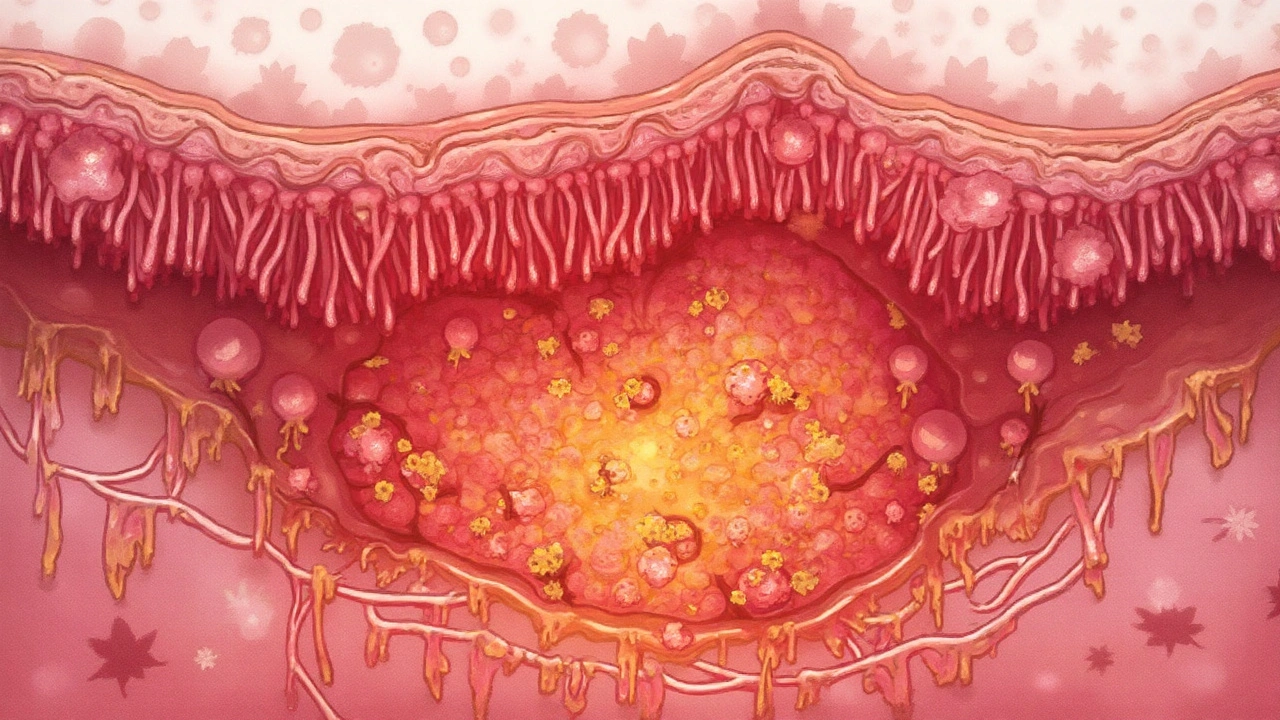

The Role of the Mucosal Barrier

The Mucosal Barrier acts like a brick wall of epithelial cells, mucus, and antimicrobial peptides. When intact, it blocks microbes and toxins. Damage-whether from radiation‑induced DNA breaks or bacterial toxins-creates gaps, letting luminal contents breach the wall.

Once the barrier is compromised, pattern‑recognition receptors (PRRs) on resident immune cells spot the invaders. The most important receptors are Toll‑like receptors (TLR2, TLR4) that recognize bacterial lipopolysaccharide and flagellin. Activation of these PRRs is the first domino that flips the switch to inflammation.

Immune Response: From Sensors to Cytokines

The moment PRRs spot danger, they recruit Cytokines-small proteins that act as messengers. Key cytokines in proctitis include:

- TNF‑α (Tumor Necrosis Factor‑alpha): amplifies vascular permeability and attracts neutrophils.

- IL‑1β (Interleukin‑1 beta): promotes fever and pain through nerve sensitization.

- IL‑6: drives acute‑phase protein production and supports B‑cell maturation.

- IL‑8: a chemokine that pulls more neutrophils into the rectal tissue.

The surge of these molecules prompts blood vessels to widen, allowing immune cells to flood the site. While this is meant to neutralize the threat, an over‑zealous response damages the epithelial lining further, creating a vicious feedback loop.

Cellular Players in the Inflamed Rectum

Several cell types dominate the microscopic battlefield:

- Neutrophils: First‑responders that release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteases, which can erode the mucosal surface.

- Macrophages: Switch between a pro‑inflammatory (M1) and healing (M2) phenotype. In acute proctitis, M1 dominates, sustaining cytokine release.

- Dendritic cells: Present antigens to T‑cells, bridging innate and adaptive immunity.

- Th17 cells: Produce IL‑17, a cytokine linked to chronic mucosal inflammation in IBD.

The balance between these cells decides whether inflammation resolves quickly or becomes chronic.

Histopathology: What the Microscope Shows

When a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy obtains a biopsy, pathologists look for characteristic patterns:

| Feature | Infectious | Radiation‑Induced | IBD‑Related |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophilic infiltrate | Prominent, often with crypt abscesses | Patchy, associated with atypical fibroblasts | Dense, may show basal plasmacytosis |

| Vasculitis | Rare | Common - endothelial swelling | Occasional |

| Crypt distortion | Yes - due to direct bacterial damage | Yes - radiation fibrosis | Yes - chronic inflammation |

These patterns help clinicians pinpoint the cause and tailor therapy.

Why Some Cases Become Chronic

Acute proctitis often clears once the trigger is removed (e.g., after antibiotics finish). Chronic cases arise when one or more of the following persist:

- Continued exposure to irritants - ongoing radiation or untreated IBD.

- Immune dysregulation - an overactive Th17 axis that refuses to shut down.

- Microbiome imbalance - loss of protective Lactobacillus species, allowing opportunistic pathogens to thrive.

Researchers now argue that chronic proctitis is less a single disease and more a syndrome of sustained mucosal immune activation.

Current Treatment Strategies

Treatment aims to break the inflammatory loop while healing the mucosa. Options differ by cause:

- Antibiotics (e.g., azithromycin) for bacterial infections.

- Topical steroids - hydrocortisone suppositories reduce cytokine production locally.

- 5‑ASA agents - mesalamine enemas inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, useful in IBD‑related proctitis.

- Hyperbaric oxygen - experimental, improves tissue oxygenation after radiation damage.

- Probiotics - specific strains (Lactobacillus rhamnosus) may restore microbiome balance.

Clinical guidelines from gastroenterology societies (e.g., AGA) recommend starting with the least systemic option, escalating only if symptoms persist beyond 4‑6 weeks.

Future Directions: Targeted Immunomodulation

Biologic drugs that block TNF‑α (infliximab) or IL‑12/23 (ustekinumab) have revolutionized Crohn’s disease. Early trials suggest they could shorten chronic proctitis when conventional therapy fails.

Another frontier is nanocarrier‑based delivery of anti‑cytokine RNAi directly to rectal tissue, minimizing systemic exposure. Although still in phase‑I trials, these approaches illustrate how a deeper grasp of the inflammation process fuels innovation.

Putting It All Together - A Practical Checklist

When you suspect proctitis, follow this quick guide:

- Take a focused history - recent radiation, sexual activity, or diarrheal illness?

- Perform a physical exam - look for external fissures or hemorrhoids.

- Order a sigmoidoscopy with biopsies - capture histology.

- Run stool PCR panels if infection is likely.

- Start cause‑specific therapy - antibiotics, steroids, or 5‑ASA.

- Re‑evaluate in 4 weeks - if no improvement, consider referral for advanced imaging or biologic therapy.

Following these steps helps you stop the inflammation before it entrenches itself.

Where to Go Next?

This article sits in the broader "gastrointestinal disorders" cluster. If you’re curious about upstream conditions, check out our pieces on ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and radiation enteritis. Downstream, learn how diet and the gut microbiome influence rectal health, or explore surgical options for refractory cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common symptoms of proctitis?

Typical signs include rectal bleeding, a constant urge to defecate, cramping, mucus discharge, and occasional fever if an infection is present.

Can proctitis resolve without medication?

If the cause is short‑term, like a bacterial gastroenteritis, the inflammation can clear once the pathogen is eradicated naturally. However, most cases benefit from targeted treatment to speed recovery and prevent complications.

Is proctitis a form of ulcerative colitis?

Proctitis can be a limited manifestation of ulcerative colitis, affecting only the rectum. When the disease spreads beyond the rectum, it’s called ulcerative colitis pancolitis.

How does radiation cause proctitis?

Radiation damages DNA in mucosal cells and triggers endothelial injury, leading to increased permeability, edema, and an inflammatory cytokine surge that mimics infection.

Are there lifestyle changes that help prevent proctitis?

Maintaining a balanced diet rich in fiber, avoiding unprotected anal intercourse, and staying up‑to‑date with pelvic radiation planning can lower risk. Probiotic supplementation may also protect the mucosal barrier.

When should I see a gastroenterologist for proctitis?

If bleeding persists beyond a week, you develop severe pain, or you have a known IBD diagnosis, specialist referral is advisable to rule out complications and consider advanced therapies.

20 Responses

so i had proctitis after that one wild weekend and honestly thought it was just hemorrhoids til the bleeding didnt stop

turns out it was shigella from a questionable hookup

antibiotics fixed it but wow the urgency was unreal

like 20x a day and no warning

also why does everything taste like metal when you're inflamed

Actually, you're missing the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in IL-1β activation - it's not just TLR4 signaling. Most clinical resources oversimplify this. The real trigger is DAMPs from epithelial necrosis, not just pathogens. Also, IL-8 is CXCL8, not just 'a chemokine' - precision matters.

Man, this is one of the clearest breakdowns of proctitis I've ever read. I work in primary care and I've seen so many patients dismissed as 'just hemorrhoids' when it's actually early IBD. The histology table alone is worth a hundred blog posts.

Also, props for mentioning hyperbaric oxygen - it's not magic, but for radiation proctitis? Game changer when standard steroids fail. My uncle’s symptoms improved after 12 sessions. No joke.

Proctitis is a thing

Let me get this straight - you're telling me that a bunch of overworked immune cells are throwing a rave in my rectum because some bacteria wandered in? And we call this medicine?

Meanwhile, my gastroenterologist wants me to swallow a pill that costs more than my rent. I get the science. I just wish the treatment matched the elegance of the explanation.

Also - yes, probiotics help. L. rhamnosus GG is the MVP. Don't waste your money on those fancy blends.

Most people don't even know what proctitis is. This is why medicine is broken.

For anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed - you're not alone. Proctitis sucks, but it's treatable. Start with the least invasive option. Talk to your doctor. Keep a symptom journal. And please, don't Google it at 2 a.m. You'll end up convinced you have cancer.

You got this.

Okay but did you guys notice how this whole article ignores the fact that glyphosate and GMOs are the real root cause of all gut inflammation? I mean, look at the data - the rise in IBD parallels the rise of Roundup use in corn crops. The mucosal barrier doesn't just 'get damaged' - it's poisoned. And they won't tell you because Big Pharma owns the journals. I've been researching this for 7 years and I've seen 37 different studies linking glyphosate to TLR4 activation - none of which are cited here. Also, my cousin's dog got proctitis after eating kibble and he's fine now on a raw diet. So yeah. Just saying.

Let’s be real - this article reads like a pharmaceutical ad disguised as science. Topical steroids? 5-ASA? Cute. But you’re still just masking symptoms. The real issue is the modern diet. Sugar, seed oils, processed everything. Your 'mucosal barrier' isn't broken - it's starved. Fix the foundation, not the symptoms. And stop pretending biologics are a cure. They’re just expensive band-aids with side effects that read like a horror novel.

Thank you for writing this. I was diagnosed with radiation proctitis after my mom’s cancer treatment. I didn’t know it was common. I thought I was the only one. This helped me understand what was happening - and I finally felt seen.

Also - hyperbaric oxygen really works. It’s not glamorous, but it’s real. And yes, the pain gets better. It just takes time.

Hey, I read this and I’m curious - are you the same person who wrote that article on Crohn’s and gut permeability last year? I think you’re onto something. Also, I’ve been having rectal pain since my last colonoscopy - should I be worried? I mean, I don’t want to overreact but I also don’t want to ignore it. Can you help?

While the structural exposition of the pathophysiological mechanisms is commendable, the article exhibits a conspicuous absence of peer-reviewed citations from the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology or the American Journal of Pathology. Without anchoring claims in the canonical literature, this piece risks degenerating into speculative narrative rather than evidence-based discourse. The omission of IL-23/Th17 axis quantification in the cytokine section is particularly troubling.

Oh great. Another 'sciencey' article that makes me feel dumb. Like, sure, TLR4 and cytokines - cool. But what does that mean for me when I'm sitting on the toilet crying because I can't stop bleeding?

Also - who wrote this? A robot? No one talks like this in real life. Just tell me what to do. Not the history of inflammation.

How dare you reduce chronic inflammation to a 'syndrome'? This isn't some buzzword for wellness influencers. This is immunological failure on a systemic level. And you're casually suggesting probiotics? Please. The microbiome is not a TikTok trend. You need to understand the epigenetic reprogramming of macrophages - not just buy a jar of Lactobacillus from Whole Foods.

Man, I love how this article connects the dots between the microscopic and the lived experience. I had proctitis after chemo and I thought I was just 'sensitive' - turns out my body was screaming. The part about Th17 cells and chronic inflammation? That’s exactly what my doctor said when I asked why it kept coming back.

Also - the checklist at the end? Print it. Tape it to your fridge. You’ll thank yourself later.

There is a fundamental flaw in this article’s assumption that inflammation is a binary response. It ignores the emerging literature on mitochondrial dysfunction as a primary driver of mucosal epithelial stress. The cytokine cascade is a downstream effect, not the origin. Furthermore, the omission of the role of the enteric nervous system in modulating immune activity renders this analysis incomplete and clinically misleading.

Thank you for presenting this with such clarity and rigor. The histopathological distinctions between infectious, radiation-induced, and IBD-related proctitis are often conflated in clinical practice. This article will serve as an excellent reference for both trainees and seasoned practitioners. The emphasis on cause-specific therapy is particularly prudent.

As someone from Canada who’s seen a lot of folks struggle with this - especially after pelvic cancer treatments - I’m glad someone’s talking about hyperbaric oxygen. It’s not widely available here, but it should be. Also, the probiotic point? Spot on. We’ve got a clinic in Toronto that’s seeing great results with VSL#3 for radiation proctitis. Worth a look.

Ugh. This is why people think doctors know everything. You’re telling me we have all these fancy drugs but we still can’t fix a 4-inch tube in the body? Pathetic. Just cut it out. That’s what they did in the 80s. Problem solved. No more cytokines, no more 'barriers,' no more 'microbiome' nonsense. Just take it out. Done.

The real tragedy isn't the inflammation - it's the collective denial. We treat symptoms like they're isolated events, but this is the body’s last scream before systemic collapse. You think proctitis is about the rectum? No. It's about the soul's quiet unraveling in a world that ignores the whispers until they become roars.

And you're still prescribing suppositories?