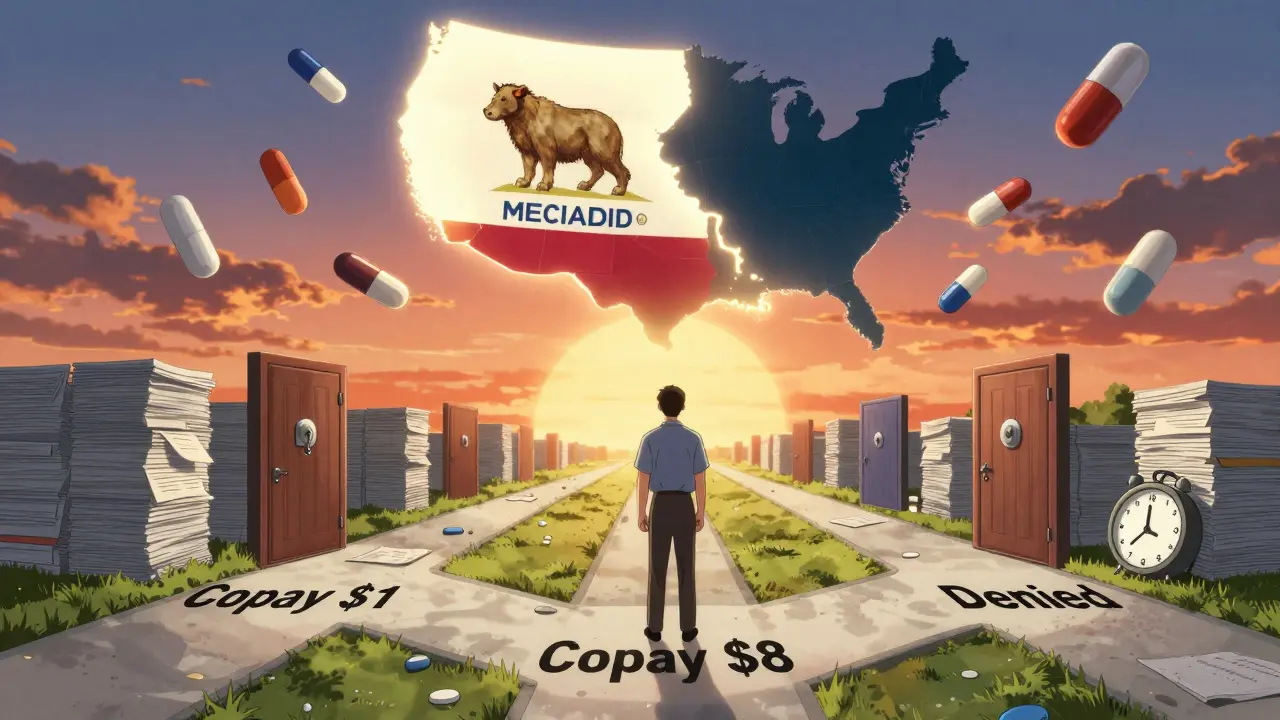

When you’re on Medicaid, getting your prescriptions filled shouldn’t be a maze. But for millions of Americans, it is. While federal law says Medicaid must cover outpatient drugs, Medicaid generic coverage varies wildly from state to state. What’s free in Colorado might need a prior authorization in Texas. What’s automatic in California could require a doctor’s note in Florida. This isn’t just paperwork-it affects whether someone takes their blood pressure pill, fills their insulin, or skips doses because the cost or process is too confusing.

Every State Covers Generics-But How?

All 50 states and Washington, D.C., cover outpatient prescription drugs under Medicaid. That’s not optional-it’s standard. But the details? That’s where things get messy. The federal government sets the floor: if a drug manufacturer is in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, the drug must be covered, unless it’s on the federal exclusion list (like fertility drugs, weight-loss meds, or erectile dysfunction pills). Beyond that, states have near-total control. That means one state can require pharmacists to swap a brand-name drug for a generic without asking the doctor. Another can let the pharmacist decide. Some states pay pharmacists more to dispense generics. Others pay so little that pharmacies refuse to participate. In Vermont, nearly every community pharmacy accepts Medicaid. In Texas, only about two-thirds do-mainly because reimbursement rates don’t cover the cost of dispensing.Automatic Generic Substitution: Not a National Rule

At least 41 states now require pharmacists to substitute a generic drug when it’s available and therapeutically equivalent. But even that’s not simple. In Colorado, the law says the generic must be dispensed unless the prescriber writes "dispense as written" or the brand is actually cheaper. In other states, like New York, substitution is allowed but not required. The pharmacist can still offer the brand if the patient asks. Therapeutic interchange is another layer. Seventeen states let pharmacists swap a prescribed drug for another generic in the same class-even if it’s not the exact same drug-if the cost difference is over $10. That’s meant to save money, but it can cause problems. A patient stabilized on one generic for seizures might get switched to another, and suddenly their seizures return. Studies show that kind of switch increases hospital visits by nearly 13%.Formularies and Tiers: What’s Covered and What’s Not

Every state uses a formulary-a list of approved drugs. Most divide drugs into tiers. Tier 1 is usually generics. Tier 2 is brand-name drugs. But here’s the catch: just because a drug is on the formulary doesn’t mean it’s easy to get. Some states have open formularies: almost any generic is covered. Others have strict preferred drug lists (PDLs). In Colorado’s Health First Colorado program, only drugs on the PDL get automatic coverage. If your doctor prescribes something off the list, you need prior authorization. And it’s not just about cost. For certain GI medications, the state requires you to try and fail on three preferred proton pump inhibitors and all preferred NSAIDs before they’ll approve a more expensive option. In California, the Medi-Cal program is simpler. Most generics are covered without step therapy or prior auth. But in states like Ohio or Pennsylvania, you might need to try two or three cheaper drugs first. This is called step therapy. At least 32 states use it for drugs like asthma inhalers, diabetes meds, and antidepressants.Prior Authorization: The Hidden Hurdle

Prior authorization is where many patients get stuck. It’s when your doctor has to call or submit paperwork to prove you need a drug before Medicaid will pay for it. For generics, you’d think this wouldn’t happen-but it does. In Colorado, most preferred generics don’t need prior auth. But if you’re on an opioid, even a generic one, you’re limited to a 7-day supply for a first prescription. And you can’t get more than eight pills a day without approval. In Michigan, prior auth is required for certain generic antibiotics if they’re not on the state’s preferred list. In Georgia, you need prior auth for any generic thyroid medication if it’s not the exact brand your doctor wrote. Approval times vary, too. Colorado responds within 24 hours. Other states take up to 72 hours. For someone running out of medication, that’s three days without treatment. Primary care doctors spend an average of 15 minutes per patient just dealing with prior auth requests. That’s over $8,200 a year in lost time per doctor.

Copayments: How Much You Pay Depends on Where You Live

Medicaid can charge copays-but only up to $8 for non-preferred generics if your income is at or below 150% of the federal poverty level. Most states charge less. Some charge nothing. In New York, most Medicaid beneficiaries pay $1 for a generic. In Florida, it’s $2. In Alabama, it’s $3. But in states like Kansas or South Dakota, you might pay $5 or $8 for a non-preferred generic. And if you’re on a managed care plan (which most Medicaid enrollees are), your copay can be even higher if the pharmacy isn’t in-network. The problem? Even a $5 copay can be too much. A 2024 study found that 1 in 5 low-income Medicaid patients skipped a refill because of cost-even for generics. That’s why some states are experimenting with $2 copays. The Medicare Two Dollar Drug List Model, which ended in March 2025, showed that when generics cost just $2, adherence to chronic meds jumped by nearly 18%.Who’s Running the Show? PBMs and State Contracts

Most states don’t handle pharmacy benefits themselves. They hire Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. These firms manage formularies, set copays, negotiate rebates, and run prior auth systems. As of early 2025, these three companies manage Medicaid pharmacy benefits in 37 states. That means your coverage might look the same in three different states-because the same PBM runs them all. But in states that manage their own programs, like California and New York, formularies are more transparent and patient-friendly. The downside? PBMs make money by steering patients toward drugs that give them the biggest rebate-not necessarily the cheapest or best for you. And they’re not required to tell you why a drug was denied. That’s why provider satisfaction with formularies varies so much. Massachusetts gets a 4.6/5 for clarity. Mississippi gets a 2.8/5.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Big changes are coming. In December 2024, CMS proposed a rule that would require Medicaid to cover anti-obesity medications-like semaglutide and tirzepatide-even though they’re brand-name drugs. That’s the first major expansion since the Affordable Care Act. If approved, it could affect nearly 5 million people. There’s also a proposed federal law to stop generic drugs from getting inflation-based rebates under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Right now, manufacturers pay back a percentage of price hikes. If that rule changes, states could lose an estimated $1.2 billion a year in rebates. That could mean higher copays, stricter formularies, or even coverage cuts. At the same time, biosimilars-generic versions of expensive biologic drugs-are starting to enter Medicaid. States are watching Michigan’s success: they used value-based pricing for a diabetes drug and cut costs by 11% without hurting adherence. More states are testing similar models.

What You Need to Do

If you’re on Medicaid and take generics:- Know your state’s formulary. Visit your state’s Medicaid website and search for "Preferred Drug List" or "PDL."

- Ask your pharmacist if they can substitute a generic-even if your doctor didn’t write it. In many states, they can.

- If a drug is denied, ask for the reason in writing. You have the right to appeal.

- Check your copay. If it’s over $5, ask if there’s a cheaper alternative on the formulary.

- If you’re switching states, get a copy of your current medication list and check the new state’s formulary before you move.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all states cover generic drugs under Medicaid?

Yes. All 50 states and Washington, D.C., cover outpatient prescription drugs, including generics, for most Medicaid enrollees. But how they cover them-through copays, prior authorization, or formulary restrictions-varies widely.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug to a generic without my doctor’s permission?

In 41 states, yes-unless the doctor specifically writes "dispense as written" or the brand is cheaper. In those states, pharmacists are required to substitute a therapeutically equivalent generic. In the other nine, substitution is allowed but not required.

Why was my generic drug denied even though it’s on the formulary?

Even if a drug is on the formulary, you might still need prior authorization. Many states require step therapy-you must try cheaper drugs first-or quantity limits. Some drugs, like opioids or thyroid meds, have extra restrictions regardless of being generic.

How much can Medicaid charge me for a generic drug?

Federal rules cap copays at $8 for non-preferred generics if your income is at or below 150% of the federal poverty level. Most states charge less-$1 to $5 is common. Some states charge nothing at all. Always check your state’s Medicaid website for exact amounts.

What should I do if I can’t get my generic medication?

Ask your pharmacist if there’s an alternative on your state’s Preferred Drug List. If not, ask your doctor to file a prior authorization request. You can also appeal a denial-every state has a process. Call your state’s Medicaid office or patient advocate line. Many states have free legal aid services for Medicaid enrollees.

Will the new anti-obesity drug coverage affect my generic medications?

Not directly. The new rule requires coverage of anti-obesity drugs, which are mostly brand-name. But if states lose rebate money from generic drugs due to upcoming federal changes, they may tighten coverage on other generics to make up the difference. Keep an eye on your state’s Medicaid updates.

11 Responses

Generic substitution in Texas is a joke. My mom skipped her insulin for three days because the pharmacy said Medicaid wouldn't cover it. Turned out the PBM just didn't want to pay the $0.50 difference. No one cares until someone dies.

Stop pretending this is about healthcare. This is about PBMs extracting rent from the poor while pretending they're saving money. Every time a state outsources pharmacy benefits, they're signing a contract to screw patients. The math doesn't lie - these companies make more off rebates than the state saves on copays. It's corporate theft wrapped in bureaucracy.

It is a fundamental failure of federalism when access to life-sustaining medication is determined by arbitrary state-level policy decisions. The Constitution grants Congress authority over interstate commerce - and pharmaceutical access across state lines is clearly within that scope. The current patchwork system is not merely inefficient - it is unconstitutional in its disparate impact.

I just cried reading this. 😭 My brother’s asthma inhaler got denied in Ohio because he had to try five cheaper ones first. He ended up in the ER. Why does bureaucracy always win when it comes to people’s lives? We need to fix this. NOW.

The entire Medicaid pharmacy infrastructure is a neoliberal dumpster fire. PBMs are rent-seeking intermediaries who have no clinical mandate, yet they control formularies with zero transparency. The so-called 'cost containment' is a mirage - it's just profit redistribution from patients to shareholders. The real solution? Nationalize the PBM function. Or better yet, abolish the rebate system entirely and implement transparent, volume-based pricing. Anything less is moral cowardice dressed in actuarial tables.

i had to call my doc 3 times just to get my blood pressure med approved in florida. they kept saying 'try this one first' but that one gave me dizziness. finally got it after 11 days. my phone battery died cause i was on hold so long. pls make it easier.

It’s ironic that we treat medication like a luxury commodity when it’s a biological necessity. The state’s role should be to ensure continuity of care, not to engineer behavioral compliance through financial friction. When we make people choose between food and pills, we’re not managing costs - we’re performing a slow violence on the vulnerable. Perhaps the question isn’t how to fix the system, but whether the system was ever meant to serve them at all.

This is why we need federal standardization. No more state-by-state chaos. No more 72-hour prior auth delays. No more $8 copays for the working poor. Medicaid is a federal program. Its benefits should be uniform. Period.

Just wanted to say - if you're reading this and you're on Medicaid, you're not alone. I've been there. I've had my insulin denied. I've had to drive 45 minutes to a pharmacy that actually accepts Medicaid. It's exhausting. But you're fighting for your life, and that matters. Keep asking for your rights. And if you can, help someone else do the same. 🙏

People who can't even manage their own health shouldn't be on Medicaid. If you're skipping pills because of a $2 copay, maybe you shouldn't be on the program at all. This is why we have welfare fraud. Lazy people gaming the system. Fix the system? No. Fix the people.

Oh wow, so now it's the patient's fault they're poor? You think insulin is optional? You think people choose to be diabetic? Your comment is why people die in waiting rooms. You should be ashamed.