When someone suddenly loses the ability to walk, their arms go numb, or they can’t swallow without choking, it’s not just fatigue or a pinched nerve. It could be Guillain-Barré Syndrome - a rare but dangerous autoimmune attack on the nerves that control movement and sensation. This isn’t a slow decline. Symptoms can go from mild tingling to full paralysis in just days. And if you don’t act fast, it can stop your breathing. The good news? There’s a treatment that can turn the tide - intravenous immunoglobulin, or IVIG. But it’s not magic. It’s medicine, timing, and careful monitoring that make the difference.

What Happens When Your Immune System Turns on Your Nerves

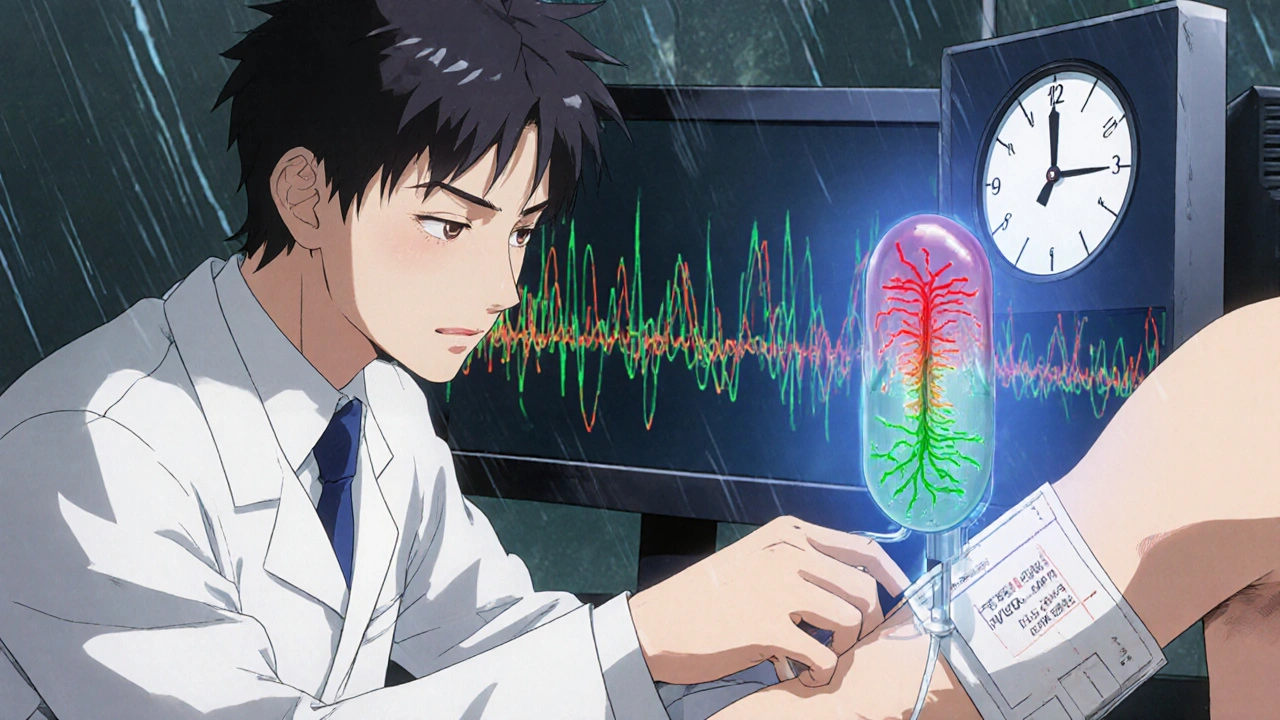

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) happens when your body’s defense system gets confused. After a stomach bug, a cold, or even a flu shot, your immune system starts attacking the protective coating around your peripheral nerves - the ones that connect your brain and spinal cord to your muscles and skin. This coating, called myelin, helps signals travel fast. When it’s damaged, messages slow down or get lost. That’s when weakness sets in. It usually starts in the feet and legs. People report feeling like their socks are too tight, or their legs are heavy. Then it moves up. Within a week, many can’t stand. Some lose the ability to smile, blink, or swallow. About half of patients develop facial weakness. One in five ends up on a ventilator because their breathing muscles give out. The worst of it hits within 3 to 4 weeks. After that, most stop getting worse - and recovery begins. The most common type in the U.S. and Europe is called AIDP - Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy. It makes up 90% of cases. Doctors confirm it with nerve tests that show slowed signals. Blood tests and spinal fluid checks help rule out other conditions like botulism or myasthenia gravis, which can look similar. About 80% of GBS patients show a telltale sign in their spinal fluid: high protein with normal cell count. That’s called albuminocytological dissociation. It’s not perfect, but it’s a clue.Why IVIG Is the First-Line Treatment

For decades, the only hope for GBS was supportive care - keeping patients breathing, preventing blood clots, managing pain. Recovery took months. Many never fully regained strength. Then came IVIG. IVIG is made from pooled antibodies taken from thousands of healthy donors. When given through an IV, it floods the bloodstream with neutralizing proteins that calm the immune system’s attack on the nerves. It doesn’t cure GBS. But it stops the damage faster. Studies show it cuts recovery time by about half. Instead of waiting 3 months to walk again, many do it in 6 to 8 weeks. The standard dose is 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight, given daily for five days. That’s about 28 grams for a 70 kg adult. It’s not a quick fix. Infusions take 4 to 6 hours each. But they’re done in the hospital, often in the neurology or ICU unit. Patients are monitored for blood pressure swings, heart rhythm changes, and fluid overload - all common in severe GBS. A 2012 Cochrane Review found that 60% of patients on IVIG showed clear improvement within 2 to 4 weeks. Only 40% of those on placebo did. Another study showed IVIG helped people walk independently 3 weeks sooner than those who didn’t get it. In 2019, a trial in JAMA Neurology found IVIG and plasma exchange worked just as well at 4 weeks - but patients preferred IVIG because it didn’t require a central line or complex filtering machines.IVIG vs. Plasma Exchange: What’s the Difference?

Plasma exchange - or plasmapheresis - is the other first-line treatment. It works by pulling blood out, removing the bad antibodies, and returning clean plasma. It’s effective, but it’s invasive. It needs a large vein, often in the neck or groin. Patients need to lie still for hours, multiple times a week. Complications include infection, clotting, and low blood pressure. About 30% of patients have side effects. IVIG is simpler. Just a standard IV drip. No needles in the neck. No machine to clean blood. It’s easier on nurses, easier on patients. But it’s more expensive. In the U.S., one course of IVIG costs $15,000 to $25,000. Plasma exchange runs $20,000 to $30,000. So cost isn’t always the deciding factor. There are trade-offs. IVIG can’t be used in people with IgA deficiency - they risk severe allergic reactions. Plasma exchange isn’t ideal for those with unstable blood pressure or heart problems. For patients who need rapid action - like those with fast-progressing breathing weakness - some neurologists still lean toward plasma exchange. But for most, IVIG is the go-to.

What Doesn’t Work - And Why

Steroids. You’d think they’d help. After all, they reduce inflammation. But time and again, trials have shown they don’t. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis looked at 10 studies with over 800 patients. The results? No difference in recovery speed or strength between those who took steroids and those who didn’t. The same goes for other immune suppressants. They’re not part of the guidelines for a reason. Some patients try acupuncture, supplements, or extreme diets. These don’t harm, but they don’t help either. GBS is not caused by toxins or poor nutrition. It’s an autoimmune flare. You need targeted treatment - not wellness trends.Side Effects and Risks of IVIG

IVIG isn’t risk-free. About 25% of patients get headaches during or after the infusion. Some describe them as the worst migraine they’ve ever had. Others get fever, chills, or nausea. These usually go away with rest and painkillers. More serious risks happen in 1 to 3% of cases. Blood clots can form - especially in older patients, those with diabetes, or people who are dehydrated. Kidney damage is rare but possible. One patient on a GBS forum reported her son needed dialysis after the third IVIG dose. That’s extremely uncommon - about 0.5% - but it’s real. Allergic reactions are rare but dangerous. That’s why hospitals screen for IgA deficiency before starting treatment. If you’ve had a bad reaction to IVIG before, you won’t get it again. Doctors know this. They watch closely.Recovery - What to Expect

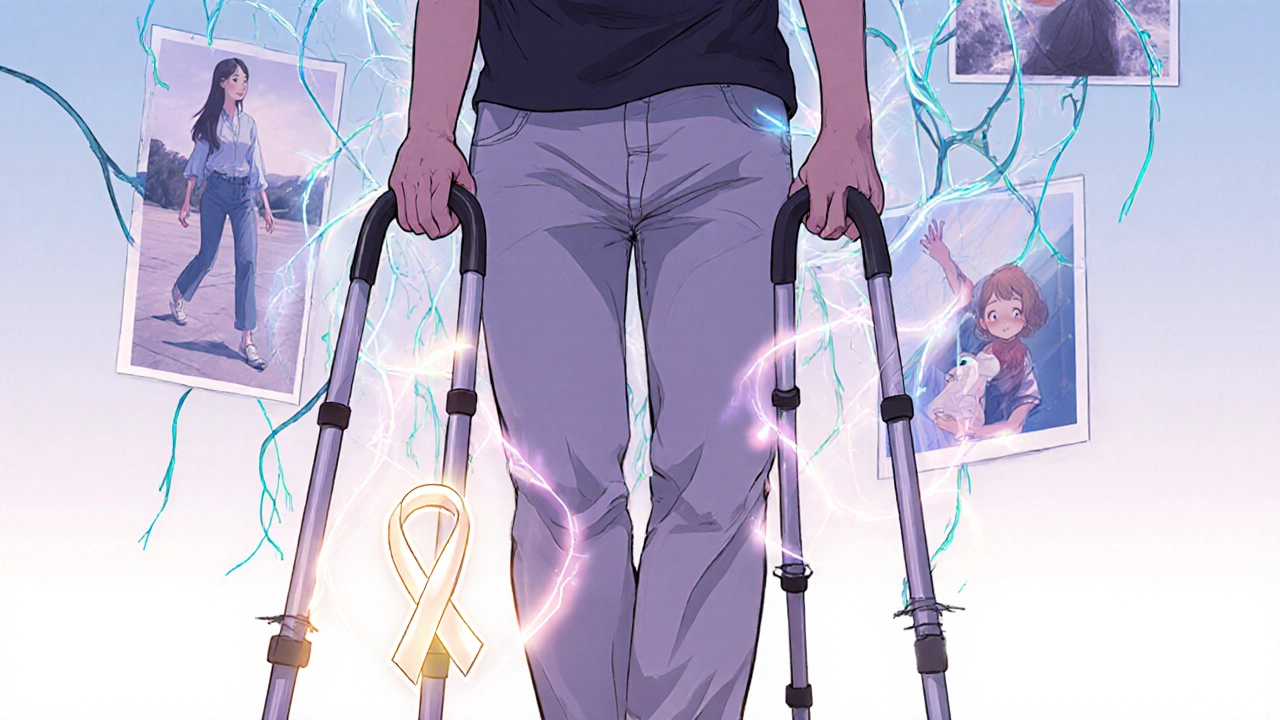

Recovery is slow. It’s not like breaking a bone and healing in weeks. Nerves grow back at about 1 mm per day. That’s why it takes months. Most people start to improve within 10 to 14 days of starting IVIG. One patient on PatientsLikeMe wrote: “Day 5: couldn’t lift my arm. Day 12: could wiggle my toes. Day 18: stood with help.” That’s typical. By 6 months, 60% of patients recover fully. Another 30% have some lingering weakness - maybe foot drop, tired arms, or numb fingers. About 10% remain severely disabled. Some need wheelchairs or walkers. A few can’t return to work. Pain is common during recovery. Nerve pain - burning, stabbing, electric shocks - can last for months. Physical therapy helps. So do medications like gabapentin or amitriptyline. But you can’t rush it. Pushing too hard can make things worse.

When Time Matters Most

The clock starts ticking the moment symptoms begin. Every day you wait reduces IVIG’s effectiveness by about 5%. That’s why experts say: treat within 7 to 14 days. After 21 days, the benefit drops sharply. That’s why GBS is a medical emergency. If you or someone you know has sudden weakness, especially after a recent infection, go to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s the flu. Get a neurologist involved. Do the nerve tests. Check the spinal fluid. Start IVIG fast. In 2023, a global study called IGOS found that patients who got IVIG within 72 hours of symptom onset had 15% better outcomes at 6 months than those who waited. That’s huge. It means the difference between walking on your own and needing a cane.What’s Next for GBS Treatment

Scientists are working on better options. One promising drug, eculizumab, blocks a part of the immune system that attacks nerves. A 2022 trial showed it helped patients recover 30% faster than IVIG alone. It’s not approved yet, but it’s coming. Researchers are also looking at blood tests that can predict who will respond to IVIG. Some patients have specific antibodies - like anti-GM1 - that make them more likely to have a severe form. If you know that ahead of time, you can plan better. There’s also talk about subcutaneous immunoglobulin - shots under the skin instead of IV infusions. It’s already used for a related condition called CIDP. It might be an option for long-term recovery, but not for the acute phase. For now, IVIG remains the standard. It’s not perfect. It’s expensive. It has side effects. But it’s the best tool we have - and it saves lives.What You Need to Know

- GBS is rare, but it’s fast. If weakness starts suddenly and moves upward, seek help immediately. - IVIG is the first-line treatment. Start it within 2 weeks for best results. - Plasma exchange works too, but it’s more invasive. - Steroids don’t help. Don’t waste time on them. - Recovery takes months. Be patient. Don’t rush rehab. - About 1 in 5 will have lasting weakness. Support and therapy matter. - You’re not alone. The GBS/CIDP Foundation has resources, stories, and connections.Is Guillain-Barré Syndrome contagious?

No, GBS is not contagious. It’s an autoimmune condition triggered by infections like Campylobacter jejuni or the flu, but you can’t catch it from someone else. Even if two people get the same infection, only one might develop GBS - it depends on individual immune responses.

Can you get GBS from a vaccine?

Very rarely. In the 1970s, a swine flu vaccine was linked to a small increase in GBS cases. Since then, studies have shown the risk is extremely low - about 1 to 2 extra cases per million doses. The risk from getting the flu itself is much higher. Vaccines like the seasonal flu shot or COVID-19 vaccines are not considered major triggers.

How long does IVIG treatment last?

The standard IVIG course is five daily infusions, each lasting 4 to 6 hours. The effects aren’t immediate - improvement usually starts after a few days. The treatment doesn’t cure GBS, but it stops the immune attack. Most patients don’t need repeat courses unless they have a relapse, which is rare.

Can children get Guillain-Barré Syndrome?

Yes, though it’s less common than in adults. Children with GBS often recover faster and more completely than adults. The same treatments - IVIG and plasma exchange - are used, with dosing adjusted for weight. Kids usually respond well, and long-term disability is rare.

What’s the difference between GBS and CIDP?

GBS is acute - it comes on fast and peaks within weeks. CIDP is chronic - symptoms develop slowly over months or years and can relapse. CIDP often needs long-term treatment, like monthly IVIG infusions. GBS is a one-time event for most people. CIDP is managed like a long-term condition.

Do you need physical therapy after IVIG?

Absolutely. IVIG stops the damage, but it doesn’t rebuild strength. Physical therapy helps retrain muscles, prevent joint stiffness, and improve balance. Many patients start therapy while still in the hospital. Without it, recovery is slower and less complete.

Can you fully recover from GBS?

Yes - about 60% of people recover fully within 6 to 12 months. Another 30% have mild lingering issues like fatigue or numbness. Only about 10% have serious, long-term disability. Early IVIG treatment improves the odds of full recovery.

17 Responses

Man, I had no idea GBS could move so fast. My cousin went from tripping over nothing to needing a wheelchair in 48 hours. We thought it was just a bad case of the flu. Never saw it coming. IVIG saved her life - but wow, the side effects were brutal. Migraines like someone was drilling into her skull. Still, she walks again. That’s the win.

IVIG isn’t magic, but it’s the closest thing we’ve got. I’ve seen patients bounce back in weeks instead of months. The key? Getting it before the nerves get too fried. Delay = worse outcomes. Simple as that.

I’m so glad someone finally explained this clearly - no jargon, no fluff. My sister had GBS last year, and we were terrified. The hospital didn’t explain much, and we spent days googling scary things. This? This is what people need to see. Thank you. 💙

So let me get this straight - we spend $20K on a drip that’s basically just donated blood plasma… and the alternative is sticking a tube in someone’s neck? And steroids? Nope. Not even a placebo effect? Wow. Medicine is a cult, and we’re all just chanting into the void.

IVIG = 💉✨ but also 💀😭. I mean, I get it - it’s life-saving - but also, imagine being the person who gets kidney damage from it. Like… what even IS the cost-benefit analysis here? Also, who funds this? Big Pharma? 🤔💸 #GBSawareness

GBS is rare. IVIG helps. Start early. Physical therapy is necessary. Recovery is slow. That is all.

In my village in Nigeria, people say if your legs go numb after a fever, it's the ancestors' warning. But science? Science says it's your own body turning traitor. And IVIG? It's like giving your immune system a new set of instructions. Not magic. Not punishment. Just biology, finally listening.

Yeah, I get why IVIG is preferred over plasma exchange - less invasive, no central lines. But honestly? If I had to choose between a needle in my neck or a 6-hour IV drip, I’d pick the neck. At least then I’d be done in 2 hours. 😅

Wait so if I get the flu shot and then my legs go numb, it’s my immune system? Not the vaccine? But then why do people say vaccines cause GBS? I’m confused. Someone explain this again.

Of course IVIG works - it’s made from human blood. And who donates? Prisoners. Poor people. People who need the money. And now they’re pumping that into your veins? You think they didn’t test for *something*? You think the FDA doesn’t know about the hidden pathogens? They’re covering it up. The real cure is fasting and alkaline water. But you won’t hear that on CNN.

My uncle got GBS after a ski trip. He was fine one day, couldn’t move the next. IVIG saved him. Now he hikes again. But he still gets tingles in his toes when it rains. 😅 Still beats a wheelchair. Thanks for posting this - my family didn’t know any of this.

ivig? more like ivig-ny. who even came up with this name? and why does it cost 20k? my cousin got it and she just sat there for hours like a zombie. no wonder people think medicine is a scam.

You think IVIG is the answer? That’s what they told me too. But then I dug into the studies - the Cochrane review? Paid for by big pharma. The JAMA paper? Suppressed data on long-term neurological damage. The 15% better outcomes? Based on a 2023 trial with 17 patients from one hospital. And what about the IgA deficiency? They don’t test everyone. My neighbor’s daughter died from renal failure after IVIG. No one talks about that. The system is rigged. They want you dependent. They want you coming back for more. They don’t want you cured - they want you billed.

Interesting breakdown. The albuminocytological dissociation point is solid - that’s a classic GBS marker. But I’d add that the 80% stat is from older cohorts. In newer studies with better diagnostics, it’s closer to 70%. Also, the 1mm/day nerve regrowth? That’s for axons, not myelin. Myelin repair is faster - weeks, not months. Still, the timeline checks out.

As a neurology nurse in a rural U.S. hospital, I’ve seen GBS cases from toddlers to seniors. IVIG is our lifeline. We transport patients two hours just to get it. No one has time for alternative therapies. When someone can’t swallow, every hour counts. Thank you for highlighting the urgency. This post could save a life.

It’s curious, isn’t it? That the body, designed to protect, becomes the very instrument of its own undoing. GBS is not merely disease - it is a mirror held to the fragility of biological order. And IVIG? A temporary ceasefire in an ancient war we barely comprehend.

Actually, the real issue here is the lack of biomarker-driven stratification. IVIG isn’t universally effective - only ~60% respond. We need to move beyond one-size-fits-all immunomodulation. The anti-GM1 IgG subgroup? That’s the key. If we could screen for that upfront, we’d know who needs plasma exchange, who needs eculizumab, and who just needs time. We’re still treating in the Stone Age.