When you're pregnant, your body works harder than ever. Hormones from the placenta help your baby grow, but they also make it harder for your insulin to do its job. That’s when gestational diabetes can show up - usually between weeks 24 and 28. It’s not your fault. It’s not because you ate too much sugar. It’s because your pancreas can’t keep up with the extra demand. About 1 in 10 pregnant women in the U.S. get it. The good news? With the right tools, you can keep your blood sugar in range and have a healthy pregnancy - just like women without it.

What Your Blood Sugar Numbers Should Be

If you’ve been diagnosed with gestational diabetes, your care team will give you specific targets. These aren’t guesses. They’re based on years of research showing what keeps babies safe. You’ll need to check your blood sugar multiple times a day. Here’s what you’re aiming for:

- Fasting or before meals: under 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L)

- One hour after eating: under 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)

- Two hours after eating: under 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L)

These numbers come straight from the American Diabetes Association’s 2023 guidelines. Going over them even once in a while isn’t a disaster - but doing it often increases risks like having a very large baby (over 9 pounds), shoulder injuries during birth, or your newborn needing extra care for low blood sugar. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s consistency.

Diet: Eat Smart, Not Just Less

You don’t need to go on a starvation diet. You need to eat smarter. Carbohydrates are your biggest challenge - they turn into glucose fastest. But they’re also your body’s main energy source. The trick is choosing the right kinds and spreading them out.

Most women need about 17 to 19 carbohydrate choices per day. One choice = 15 grams of carbs. That means:

- Breakfast: 3 choices (45g carbs)

- Lunch: 3 choices (45g carbs)

- Dinner: 3 choices (45g carbs)

- Snacks: 2-3 choices total (30-45g carbs)

Choose complex carbs: whole grains, legumes, oats, sweet potatoes, and non-starchy vegetables. Skip white bread, sugary cereals, and fruit juice. Pair every carb with protein or fat to slow the spike. An apple alone might send your sugar up. An apple with a tablespoon of peanut butter? That’s a win. Studies show this combo cuts the glucose spike by about 30%.

There’s also a simple eating order that helps: eat protein first (chicken, eggs, tofu), then vegetables, then carbs. A UCSF Health survey found 74% of women saw their post-meal sugar drop by 25 to 40 mg/dL using this method. It’s not magic - it’s physics. Protein and fiber slow digestion, giving your body more time to handle the sugar.

Move Your Body - Even Just a Little

Exercise isn’t optional. It’s medicine. Walking for 30 minutes, five days a week, can drop your blood sugar by 20 to 30 mg/dL after meals. You don’t need to run a marathon. A brisk walk after lunch or dinner is enough. Swimming and prenatal yoga are great too - low impact, high benefit.

One of the most powerful tricks? Walk for 15 to 30 minutes right after eating. That’s when your blood sugar peaks. Movement pulls glucose out of your bloodstream and into your muscles, where it’s used for energy. A woman in Melbourne shared on Reddit that her fasting numbers dropped 15 to 25 mg/dL just by walking after breakfast. She didn’t change her food - just her timing.

When Diet and Exercise Aren’t Enough

Most women - 70% to 85% - get their numbers under control with food and movement alone. But if your blood sugar stays high after a few weeks, your doctor will talk about medication.

Insulin is the gold standard. It doesn’t cross the placenta, so it’s safe for your baby. Many women worry about needles. But insulin pens are small, quiet, and easy to use. Most people get used to them in a few days. You might start with one shot a day, usually at bedtime, to control morning highs.

Some doctors prescribe metformin. It’s an oral pill, which some women prefer. But it does cross the placenta, and research is still mixed on long-term effects. In the MiTy trial, 30% of women on metformin still needed insulin later. So it’s not a replacement - more of a backup.

Monitoring: The Key to Control

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. That’s why checking your blood sugar 4 to 6 times a day is so important. You’ll use a glucometer. Make sure it’s calibrated with control solution every day. Write down your readings with what you ate and when you moved. Patterns matter more than single numbers.

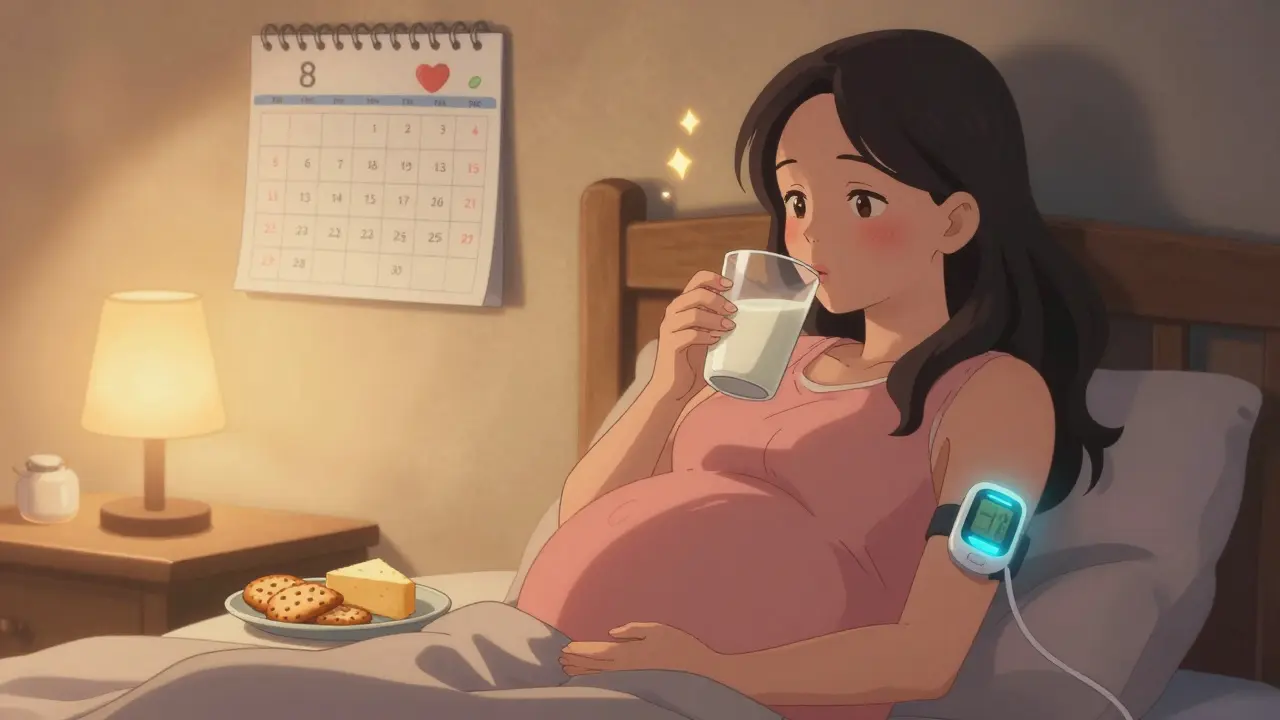

Fasting highs are common - happening in nearly half of women with gestational diabetes. That’s often caused by hormones released overnight. A bedtime snack with 15g carbs and protein (like 6 crackers and 1 oz of cheese) can help stabilize your morning levels.

Some women use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). These are small sensors worn on the arm that track sugar levels 24/7. They’re not yet standard for gestational diabetes, but adoption is rising fast - from 5% in 2018 to 22% in 2022. In women with Type 1 diabetes, CGMs cut the risk of having a very large baby by 39%. Even if you don’t have one now, ask your provider if it’s an option.

Emotional Health Matters Too

Getting diagnosed with gestational diabetes can feel overwhelming. A DiabetesSisters survey found 68% of women felt anxious or guilty at first. Some feared insulin. Others felt judged by family members who said, “You ate too much sugar.”

But here’s the truth: gestational diabetes is not a punishment. It’s a signal. And with support, you can handle it. Women who got clear, consistent education from a certified diabetes care specialist were 85% more satisfied with their care. If your provider doesn’t offer this, ask. You deserve it.

Online communities like Reddit’s r/GestationalDiabetes are full of real tips: using MyFitnessPal to track carbs, setting phone alarms for checks, meal prepping snacks ahead of time. You’re not alone. Thousands of women have walked this path - and most came out with healthy babies and no long-term issues.

What Happens After the Baby is Born

After delivery, your blood sugar will likely return to normal. About 70% of women see their gestational diabetes disappear. But here’s the catch: half of them will develop Type 2 diabetes within 10 years.

That’s why follow-up is non-negotiable. You need a glucose test 6 to 12 weeks after birth. It’s a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test - same as the one used to diagnose it. If your fasting number is above 126 mg/dL or your 2-hour number is above 200 mg/dL, you have Type 2 diabetes. If it’s borderline, you have prediabetes.

But you can change that future. The TODAY2 study showed that losing just 5 to 7% of your body weight in the first year after birth cuts your risk of Type 2 diabetes by 58%. That’s not about extreme diets. It’s about keeping up with healthy eating, staying active, and checking in with your doctor every two years.

What Doesn’t Work

Some things people try don’t help - and might even hurt.

- Skipping meals to “lower sugar” - this causes dangerous swings and can make fasting highs worse.

- Going low-carb or keto - not recommended during pregnancy. Your baby needs glucose for brain development.

- Waiting until after 28 weeks to get tested - early diagnosis means better control. Most clinics screen between 24 and 28 weeks, but if you’re high risk (overweight, family history, previous GDM), ask for testing earlier.

- Checking glucose less than four times a day - women who check less often have 2.3 times higher risk of NICU admission for their babies.

Also, avoid conflicting advice. Some OBs give one diet plan. Endocrinologists give another. That’s confusing. Find one provider - usually a certified diabetes care specialist - who coordinates your care. Don’t be afraid to ask: “Who’s in charge of my plan?”

You’ve Got This

Gestational diabetes isn’t a life sentence. It’s a temporary condition with a clear path forward. You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to be consistent. Eat balanced meals. Move daily. Check your numbers. Ask for help when you need it. And remember - every small choice you make now is helping your baby grow strong and setting you up for a healthier future.

Can gestational diabetes harm my baby?

If left unmanaged, gestational diabetes can lead to a large baby (over 9 pounds), which increases the risk of birth injuries, C-sections, and neonatal low blood sugar. It can also raise the chance of preterm birth and preeclampsia. But when blood sugar is kept within target ranges, these risks drop to nearly the same levels as pregnancies without gestational diabetes.

Will I have diabetes after my baby is born?

About 70% of women see their blood sugar return to normal after delivery. But half of those women will develop Type 2 diabetes within 10 years. That’s why a follow-up glucose test 6 to 12 weeks after birth is critical. Making lifestyle changes - eating well, staying active, and maintaining a healthy weight - can reduce that risk by more than half.

Do I need to take insulin if I have gestational diabetes?

Not everyone does. About 70% to 85% of women manage their blood sugar with diet and exercise alone. If your numbers stay high after a few weeks, your doctor may recommend insulin. It’s safe for your baby and doesn’t cross the placenta. Many women are nervous about needles, but insulin pens are simple to use and most people adjust quickly.

Can I eat fruit with gestational diabetes?

Yes, but portion and pairing matter. One small piece of fruit (like an apple or orange) counts as one carb choice (15g). Always eat it with protein or fat - like a handful of nuts or a spoon of Greek yogurt - to slow the sugar spike. Avoid fruit juice, dried fruit, and smoothies, which spike blood sugar fast.

How often should I check my blood sugar?

Most women check 4 to 6 times a day: fasting in the morning, and 1 to 2 hours after each meal. This helps spot patterns and adjust food or activity. Women who check less than four times daily have more than twice the risk of complications. Record each reading with what you ate - this helps your care team spot trends.

Is gestational diabetes my fault?

Absolutely not. Gestational diabetes is caused by hormones from the placenta that block insulin. It’s not about eating too much sugar or being overweight - although those can increase your risk. Many women who eat healthy and stay active still get it. It’s a common condition, not a personal failure.