Statin Tolerance Calculator

Find out how your SLCO1B1 gene variant affects your statin tolerance and get personalized recommendations.

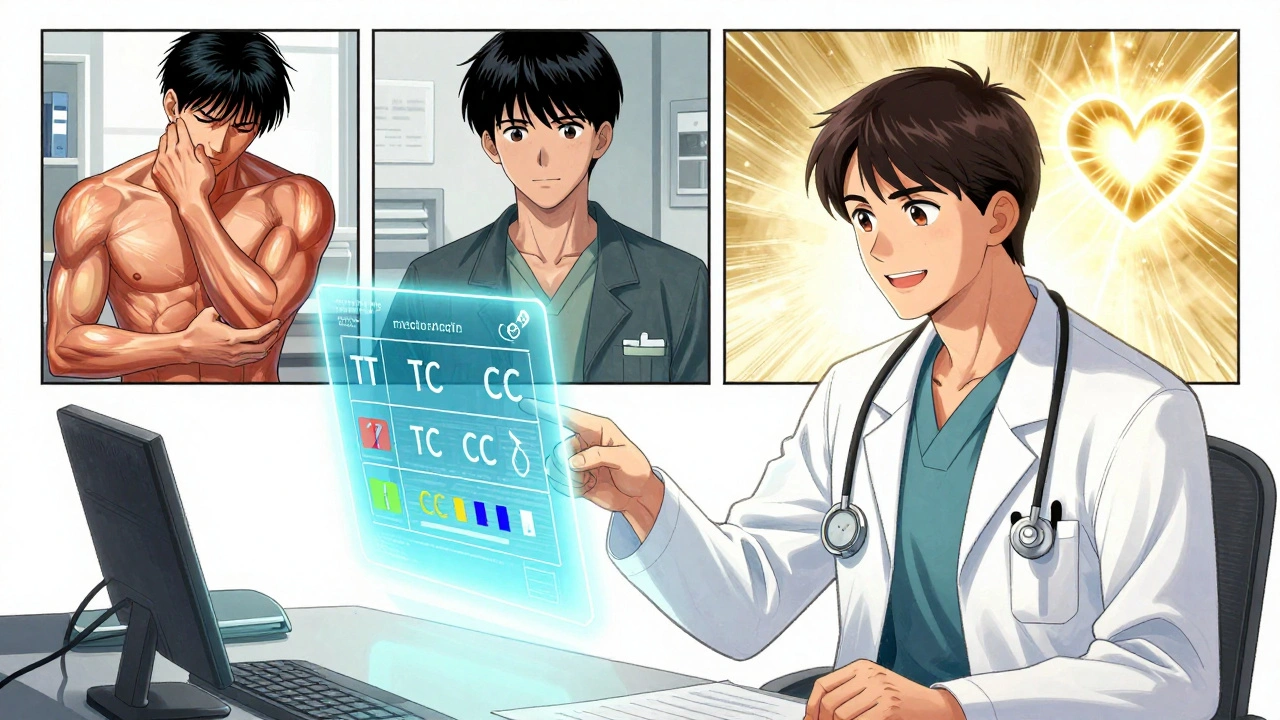

Select your genotype to see personalized recommendations

For millions of people taking statins to lower cholesterol and prevent heart attacks, muscle pain isn’t just an inconvenience-it’s a dealbreaker. About 1 in 4 patients stop taking their statin because of muscle aches, weakness, or cramps. But what if the problem isn’t the drug itself, but your genes?

Why Some People Can’t Tolerate Statins

Statin drugs like simvastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin work by blocking cholesterol production in the liver. They’ve saved countless lives, but they don’t work the same for everyone. Muscle-related side effects, known as statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), are the most common reason people quit. Many assume it’s just bad luck, aging, or overexertion. But research now shows genetics play a major role.The key player is a gene called SLCO1B1. This gene makes a protein that shuttles statins into the liver, where they’re meant to work. If your version of this gene has a specific variant-called c.521T>C, or rs4149056-your body doesn’t clear statins properly. That means more of the drug stays in your bloodstream, increasing the chance of muscle damage.

People with two copies of this variant (CC genotype) have a 4.5 times higher risk of severe muscle injury when taking high-dose simvastatin. Even one copy (TC genotype) raises the risk by 2.6 times. This isn’t theoretical-it’s backed by large studies, including a landmark 2008 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. The problem? Most doctors still don’t test for it.

Not All Statins Are Created Equal

Here’s the important part: this genetic risk doesn’t apply to all statins. The SLCO1B1 variant is strongly linked to simvastatin, especially at the 80mg dose. But for atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, the same genetic risk doesn’t show up in major studies. That means if you’ve had muscle pain on simvastatin, switching to another statin might solve the problem-without needing to stop cholesterol-lowering treatment entirely.Pravastatin and fluvastatin are good alternatives. They don’t rely as heavily on the SLCO1B1 transporter, so even if you have the high-risk genotype, your risk of muscle side effects drops by up to 80% compared to simvastatin. A 2021 study at Mayo Clinic found that 78% of patients who had previously quit statins due to muscle pain were able to restart therapy successfully after switching based on their genetic results.

But here’s the catch: if your doctor doesn’t know about your genetics, they might keep prescribing simvastatin-or worse, tell you the pain is “all in your head.” That’s why testing matters.

What Pharmacogenomics Testing Actually Tells You

Pharmacogenomics testing for statins looks at your DNA to find variants like SLCO1B1 rs4149056. The test is simple: a cheek swab or blood sample sent to a lab. Results come back in about a week. The report doesn’t just say “positive” or “negative.” It tells you your exact genotype-TT, TC, or CC-and what that means for each statin.For example:

- TT (normal): No increased risk. Simvastatin can be used normally.

- TC (heterozygous): Moderate risk. Avoid high-dose simvastatin (80mg). Lower doses or alternative statins are safer.

- CC (homozygous): High risk. Avoid simvastatin 80mg entirely. Even lower doses carry increased risk. Switch to pravastatin, rosuvastatin, or atorvastatin.

These are the exact recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), the gold standard for drug-gene guidelines. The guidelines are updated regularly and freely available to any clinician.

Other genes like CYP2D6, ABCB1, and GATM are also being studied, but none have the same level of proof or clinical guidance as SLCO1B1. Right now, if you’re getting tested for statin tolerance, SLCO1B1 is the only gene that should change your treatment plan.

Does Testing Actually Help People Stay on Their Meds?

You might think: if the science is solid, why isn’t everyone getting tested?Because real-world results are mixed. A 2020 Harvard study gave SLCO1B1 results to doctors treating patients with prior statin intolerance. They expected adherence to improve. It didn’t. Patients still reported muscle pain, and many still quit statins. Why? Because genetics isn’t the whole story.

SLCO1B1 explains only about 6% of statin muscle side effects. That means 94% of the risk comes from other factors: age, kidney function, thyroid issues, alcohol use, drug interactions (like with fibrates or certain antibiotics), or even vitamin D deficiency. So even if you have the low-risk genotype, you can still get muscle pain. And if you have the high-risk genotype, you might still tolerate simvastatin fine.

But here’s what the data does show: for people who’ve already had muscle symptoms, knowing their genotype helps doctors pick a safer statin. One study found that patients who got genotype-guided advice were nearly 20% more likely to stay on statin therapy than those who didn’t.

Who Should Get Tested?

Testing isn’t for everyone. The American College of Cardiology doesn’t recommend routine testing for all patients starting statins. But here’s who should consider it:- You had muscle pain on one statin and stopped taking it.

- You’re being prescribed high-dose simvastatin (80mg) and have unexplained muscle aches.

- You have a family history of statin intolerance.

- You’re considering restarting a statin after quitting due to side effects.

If you’ve never taken a statin and have no symptoms, testing isn’t needed. But if you’ve had trouble with statins before, this test could be the key to getting back on track.

Cost, Insurance, and Getting Tested

As of 2025, standalone SLCO1B1 testing costs between $150 and $400 out-of-pocket. Many insurance plans still don’t cover it-only about 28% of commercial insurers did in 2022. Medicare rarely covers it unless it’s part of a broader pharmacogenomic panel tied to a specific clinical situation.Some large health systems, like Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente, offer pre-emptive testing as part of routine care. If you’re in one of those systems, you might already have your results in your electronic health record. Ask your doctor: “Do you have my pharmacogenomic data on file?”

Commercial labs like OneOme and Color Genomics offer direct-to-consumer tests that include SLCO1B1. But be careful: some of these tests give you raw data without interpretation. You’ll need a doctor or pharmacist who understands pharmacogenomics to explain what it means for your treatment.

What’s Next for Genetic Testing and Statins?

The future isn’t just about one gene. Researchers are building polygenic risk scores that combine SLCO1B1 with 10-15 other genetic markers linked to muscle symptoms. Early results show these scores can predict risk better than SLCO1B1 alone, raising accuracy from 58% to 67%.Also, new tools are being built into electronic health records. Systems like Epic and Cerner now automatically warn doctors if they try to prescribe simvastatin 80mg to someone with a CC genotype. That’s a big step toward making this testing routine, not optional.

The Statin Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium, launched in 2023, aims to standardize testing across 50 U.S. hospitals by 2025. If successful, this could become standard care within the next five years.

Bottom Line: What You Can Do Today

If you’ve quit statins because of muscle pain, don’t assume you can’t take them. You might just need a different one.Here’s what to do:

- Ask your doctor if you’ve ever been tested for SLCO1B1. If not, ask if testing is right for you.

- If you’ve had muscle pain on simvastatin, ask about switching to pravastatin, rosuvastatin, or atorvastatin-those are safer options if you have the high-risk gene.

- If you’re starting statins and have a family history of intolerance, consider getting tested before you begin.

- Don’t accept muscle pain as normal. There are better ways to manage it than quitting your medication.

Statins reduce heart attack risk by up to 30%. Giving them up because of muscle pain isn’t just a personal choice-it’s a health risk. With the right genetic insight, you might not have to choose between your heart and your muscles anymore.

10 Responses

So let me get this right-my muscles hurt because my DNA’s got a glitch??! I’ve been blaming the gym, my old knees, even my cat for stepping on me… turns out it’s my genes being petty. 😅

And now they want me to pay $400 just to find out if I’m genetically cursed? My insurance won’t cover it, so I’m stuck with simvastatin and aching thighs. This is healthcare for the rich, folks.

The data is solid but oversimplified. SLCO1B1 explains a fraction of the variance. Ignoring comorbidities like hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, or statin-fibrate interactions is reckless clinical practice. Genetics is not a magic bullet-it’s one piece of a very messy puzzle.

Guys-this changed my life!! I quit statins for 3 years because of muscle cramps so bad I couldn’t walk my dog. Got tested through my health system, turned out I was CC genotype. Switched to rosuvastatin and BAM-no pain, my cholesterol’s down, and I’m hiking again!! 🙌

Don’t give up! Talk to your doc, ask about testing, and don’t let them brush it off as ‘just aging.’ You deserve to feel good AND stay heart-healthy!!

You all are missing the real issue-Big Pharma doesn’t want you to get tested because they make more money selling you the same statin over and over. Why sell you a $150 test when they can keep selling you simvastatin and collecting co-pays? And don’t even get me started on how the labs own the data. Your DNA’s being sold to advertisers next.

Also, your doctor probably didn’t even know what SLCO1B1 is. They went to med school 20 years ago and still think statins are ‘just cholesterol pills.’

As an Aussie who’s seen this play out in our public health system, I can confirm-this isn’t science fiction. We’ve had pharmacogenomic testing integrated into our primary care for years, especially for clopidogrel and warfarin. Statins? Slowly catching on. The real barrier isn’t the science-it’s bureaucracy.

Doctors are overworked. They don’t have time to interpret genetic reports. We need automated alerts in EHRs, not just fancy research papers. The tech exists. The will? Not so much.

I’ve worked with patients who’ve been on statins for decades, only to stop because of muscle pain-and then end up in the ER with a heart attack six months later. This isn’t about convenience. It’s about survival.

Genetics doesn’t absolve us from lifestyle, but it gives us a roadmap. If you’ve had muscle pain, don’t assume it’s your fault. Don’t assume it’s the drug’s fault. Ask for the test. Ask for a different statin. Ask for help.

You’re not broken. Your body just needs a different key.

Wait… so if I have the CC genotype, does that mean my DNA is secretly controlled by the Illuminati? Because I’ve been on simvastatin for 8 years and never had a problem. But now I’m paranoid my fridge is watching me. 🤔👁️

Also-why do they only test ONE gene? What if my liver hates statins because I drank kombucha in 2017? I think they’re hiding the real truth.

While the clinical utility of SLCO1B1 genotyping is supported by evidence-based guidelines from CPIC, its adoption remains suboptimal due to systemic barriers including lack of provider education, insufficient reimbursement, and fragmented integration into electronic health records. A multidisciplinary approach involving pharmacists, genetic counselors, and clinical informaticists is essential to bridge this implementation gap.

Stop treating this like a science fair project. People are dying because doctors are too lazy to read a genetic report. This isn’t ‘maybe try this.’ This is: if you prescribe simvastatin 80mg to someone with CC, you’re playing Russian roulette with their muscles-and their heart.

Doctors who ignore this are negligent. Period.

Okay, so my DNA’s got a glitch that makes me a walking statin landmine? Sweet. Now I’m basically a biohacker with a genetic curse. 🧬💥

I’ve got the CC genotype, switched to pravastatin, and now I feel like a superhero-no muscle zombies, no guilt, no ‘maybe it’s all in your head’ BS. I’m living proof that your genes don’t define your fate-they just give you the cheat codes.

And if your doc says ‘it’s just aging’? Tell them to read the NEJM. Or better yet-send them my test results with a sticky note that says ‘I’m not broken. You’re just outdated.’