Steroid-Induced Hyperglycemia Risk Calculator

When you’re prescribed corticosteroids like prednisone or dexamethasone, it’s usually because you need powerful relief from inflammation - whether it’s from asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, or a flare-up of Crohn’s disease. But what many patients don’t realize is that these same drugs can send blood sugar levels soaring, even in people who’ve never had diabetes before. This isn’t just a side effect - it’s a metabolic disruption with real risks, and it happens faster and more often than most doctors expect.

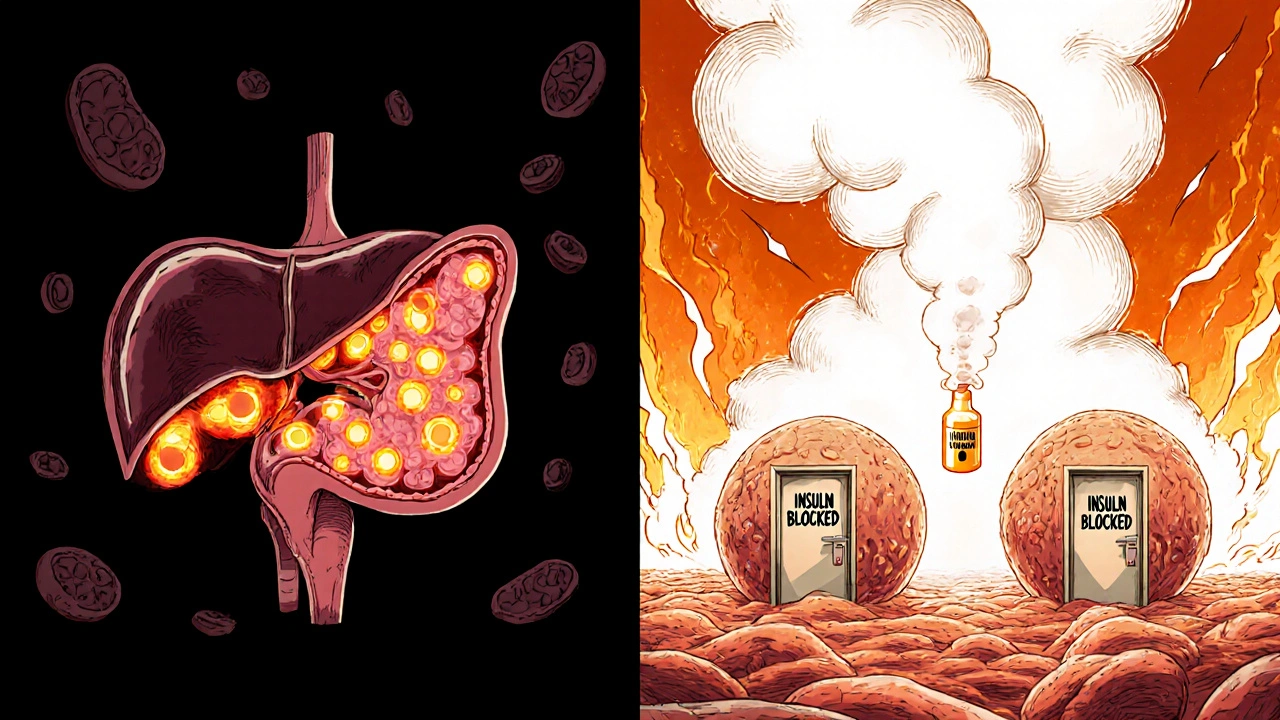

Why Corticosteroids Raise Blood Sugar

Corticosteroids don’t just reduce swelling - they mess with how your body handles glucose. Think of your body as a factory that normally uses insulin to move sugar from your blood into your muscles and fat for energy. Corticosteroids shut down that system in three key places: your liver, your muscles, and your pancreas.

In your liver, these drugs tell your body to pump out more glucose - up to 40% more - by turning on enzymes that create sugar from scratch. At the same time, your muscles become blind to insulin. Normally, insulin opens the door for glucose to enter muscle cells. With steroids, that door stays locked. Studies show glucose uptake drops by about 30%, meaning sugar just piles up in your bloodstream.

Then there’s your pancreas. The cells that make insulin - called beta cells - start to slow down. Corticosteroids reduce the production of GLUT2 and glucokinase, two proteins your beta cells need to sense blood sugar and respond with insulin. On top of that, fat breakdown increases, flooding your blood with free fatty acids that further block insulin action. It’s not just insulin resistance - it’s insulin shortage too. That’s why steroid-induced diabetes behaves differently from type 2 diabetes. You’re not just resistant - you’re also running low on insulin.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on steroids gets high blood sugar. But certain people are far more likely to. If you’re over 50, overweight (BMI 25 or higher), or have a family history of diabetes, your risk jumps. Even more telling: if you’ve had gestational diabetes, your chance of developing steroid-induced diabetes is more than four times higher.

Dose matters. Taking 7.5 mg of prednisone daily or more raises your risk by over three times. Dexamethasone is even worse - at equivalent anti-inflammatory doses, it’s six to eight times more likely to spike blood sugar than prednisone. And it’s not just about the dose - it’s how long you’re on it. For every week beyond the first two, your risk climbs by 12%. That’s why someone on a two-week course for a flare-up might be fine, but someone on monthly pulses for lupus could develop persistent high blood sugar.

People with kidney problems are also at higher risk. If your eGFR is below 60, your body clears steroids slower, and the metabolic impact lasts longer. Even if you’ve never had diabetes, these factors add up. In fact, 20% to 50% of patients on high-dose steroids develop hyperglycemia - and nearly half of those cases go undetected because symptoms are subtle or mistaken for steroid side effects.

What the Symptoms Look Like (And What They Don’t)

High blood sugar from steroids doesn’t always come with the classic signs. Sure, some people feel thirsty, pee constantly, or get unusually tired. But here’s the catch: 40% of patients show no symptoms at all. That’s why routine blood sugar checks are critical - especially in hospitals or for those on long-term therapy.

And it’s easy to confuse steroid side effects with diabetes symptoms. Increased hunger? Common with steroids. Weight gain? Almost universal. Blurred vision? Could be high sugar - or just fluid shifts from the drug. Mood swings? Steroids cause those too. This overlap is why so many patients aren’t tested. Reddit users in r/diabetes report that 68% were never warned about this risk before starting steroids. By the time they notice their blood sugar is high, it’s already been weeks.

How Doctors Should Manage It

Managing steroid-induced hyperglycemia isn’t about guessing. It’s about timing, monitoring, and matching treatment to the drug’s schedule.

The NIH recommends checking blood sugar at least twice a day for anyone on prednisone 20 mg or more. If fasting glucose hits 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) or random readings go above 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L), it’s time to act. For patients with existing type 2 diabetes, insulin needs often double during steroid therapy.

Insulin is the most reliable tool. Basal insulin - the long-acting kind - is usually increased by 20% for every 10 mg of prednisone above 20 mg/day. Rapid-acting insulin is given with meals, using a 1 unit per 5-10 grams of carb ratio. But timing matters. Steroids peak in effect 4 to 8 hours after you take them, so your highest blood sugar often comes in the afternoon or evening, not the morning. That’s why checking only at breakfast misses the real problem.

Oral meds like sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide) can help by forcing the pancreas to release more insulin. But they’re risky when steroids are tapered. As the steroid dose drops, insulin production doesn’t bounce back immediately - but the sulfonylurea keeps pushing. That’s when dangerous low blood sugar happens. In fact, 37% of adverse events in steroid patients on these drugs occur during tapering, not during high-dose therapy.

What Happens When You Stop Steroids?

Here’s the good news: steroid-induced diabetes is often temporary. Once the drug is stopped, blood sugar usually returns to normal within 3 to 5 days. But too many patients keep taking diabetes meds out of habit - or because their doctor didn’t explain it was temporary.

That’s a problem. Continuing insulin or oral meds after stopping steroids can lead to hypoglycemia, especially if the patient is eating less or moving more as they recover. In one study, 63% of patients were still on diabetes medications a month after stopping steroids - even though their blood sugar had normalized. Clear communication is key. Patients need to know: this isn’t your fault, it’s the drug’s effect, and it should reverse.

New Tools and Future Hope

There’s progress on the horizon. In 2023, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes launched a mobile app called STEROID-Glucose. It links your steroid dose to your blood sugar readings and suggests insulin adjustments in real time. Early results show a 32% drop in hyperglycemic events.

The NIH is also testing GLP-1 receptor agonists - drugs like semaglutide - for steroid-induced diabetes. Early data suggests they lower blood sugar just as well as insulin but with less risk of low blood sugar. That’s a big deal, especially for older patients who are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia.

Long-term, researchers are working on new steroid-like drugs that fight inflammation without wrecking metabolism. One compound, XG-201, reduced hyperglycemia by 65% in trials compared to prednisone, while keeping the same anti-inflammatory power. If approved, this could change everything for patients with autoimmune diseases who need long-term treatment.

The Bigger Picture

Corticosteroids are used by 1-2% of the population every year. Among people over 65, that number climbs to 8-10%. In hospitals, up to 60% of patients on high-dose steroids develop hyperglycemia - adding an average of two extra days to their stay and $3,000 to their bill. Primary care doctors miss monitoring in 35% of cases. That’s not negligence - it’s a system gap. Most guidelines assume diabetes is chronic. But steroid-induced diabetes is acute, reversible, and often invisible.

The American Diabetes Association and Endocrine Society updated their guidelines in 2022 to push for proactive monitoring, individualized treatment, and patient education. But without clear protocols, it’s still hit or miss. If you’re prescribed corticosteroids, ask: "Will you be checking my blood sugar? What should I do if it’s high?" Don’t wait for them to bring it up. You’re not overreacting - you’re being smart.

The future of steroid therapy isn’t just about better drugs - it’s about better awareness. Steroid-induced diabetes isn’t rare. It’s predictable. And with the right checks, it’s preventable.

Can corticosteroids cause diabetes in someone who’s never had it before?

Yes. Corticosteroids can trigger steroid-induced diabetes in people without prior diabetes. This happens in 10-30% of patients on high-dose therapy, and up to 50% show some level of hyperglycemia. It’s not a permanent condition for most - blood sugar usually returns to normal after stopping the drug - but it requires active monitoring and sometimes treatment during therapy.

How soon after starting steroids does blood sugar rise?

Blood sugar can rise within 24 to 48 hours of starting high-dose corticosteroids. The peak effect usually occurs 4 to 8 hours after taking the dose, which is why afternoon or evening glucose readings are often the highest. That’s why checking only fasting glucose in the morning can miss the problem entirely.

Is insulin the best treatment for steroid-induced hyperglycemia?

Insulin is the most effective and safest option for most patients, especially those on high doses or with existing diabetes. It can be tailored to match the steroid’s timing and dose. Oral medications like sulfonylureas are riskier because they can cause low blood sugar when steroids are tapered. GLP-1 agonists are emerging as a promising alternative with fewer hypoglycemia risks.

Do I need to stay on diabetes medication after stopping steroids?

Usually not. Blood sugar typically returns to normal within 3 to 5 days after stopping corticosteroids. Continuing diabetes meds after that can lead to dangerous low blood sugar. Always have your doctor review your medications after steroid therapy ends - don’t assume you still need them.

Why don’t doctors always warn patients about this?

Many providers assume hyperglycemia only affects people with existing diabetes, or they underestimate how common and rapid steroid-induced spikes can be. A 2022 audit found 35% of patients on long-term steroids in primary care received no glucose monitoring. Patient reports also show that 68% weren’t warned about this risk before starting treatment. Better education and standardized protocols are needed.

13 Responses

I was on prednisone for a month last year and didn’t realize my thirst and fatigue weren’t just ‘steroid side effects’ until my sugar hit 280. My doctor never mentioned it. Learned the hard way - always ask for a glucose check if you’re on steroids. 🙃

It is imperative to underscore the clinical significance of steroid-induced hyperglycemia as a distinct pathophysiological entity, separate from type 2 diabetes mellitus. The metabolic dysregulation induced by glucocorticoids is multifactorial, involving hepatic gluconeogenesis, peripheral insulin resistance, and pancreatic beta-cell suppression. Proactive monitoring protocols are not merely advisable - they are ethically obligatory in high-risk populations.

Insulin is the real MVP here. 😎 I watched my dad go from 0 to insulin in 3 days on high-dose dexamethasone. They didn’t test him until his HbA1c was 9.2. He’s fine now, but if they’d just checked his sugars daily, he wouldn’t have felt like garbage for a week. Tell your doc: ‘Check my glucose, not just my lungs.’

lol american doctors be like ‘oh u got steroids? ur sugar gonna go up? lol no biggie’ meanwhile in india we know steroids are poison for diabetics. they give it only if ur dying. u guys just pop pills like candy. also why u always need insulin? just eat less sugar dumbass

If you’re on steroids and you’re feeling weirdly tired, hungry, or peeing all the time - don’t brush it off. You’re not being dramatic. Your body is screaming. Ask for a glucometer. Even if you’re ‘not diabetic.’ I’m not a doctor, but I’ve seen too many people get blindsided by this. You deserve to be warned.

It’s fascinating how the medical establishment still treats steroid-induced hyperglycemia as an afterthought. The fact that 68% of patients report being uninformed speaks to a systemic failure of physician education. Furthermore, the reliance on insulin - while clinically sound - reflects a lack of innovation. Why aren’t we prioritizing GLP-1 agonists as first-line? The data is clear. This isn’t medicine. It’s triage.

THEY PUT IT IN THE MEDS ON PURPOSE. THE PHARMA COMPANIES KNOW STEROIDS MAKE YOU SICK SO YOU’LL STAY ON DIABETES DRUGS FOREVER. THEY OWN THE DOCTORS. I READ A THREAD WHERE A NURSE SAID THEY GET BONUSES FOR PRESCRIBING INSULIN. YOU THINK THIS IS AN ACCIDENT? IT’S A SCAM. CHECK THE FDA RECORDS. THEY’RE HIDING SOMETHING.

The mechanistic interplay between glucocorticoid receptor signaling and hepatic PEPCK upregulation is well-documented in the literature, but what’s underappreciated is the adipokine-mediated suppression of adiponectin, which exacerbates insulin resistance. Coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle, this creates a perfect storm for hyperglycemia. The clinical implications for long-term users warrant a paradigm shift toward preemptive metabolic profiling.

It’s astonishing how casually clinicians dismiss this. A 2022 study in *The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology* showed that steroid-induced hyperglycemia increases 30-day readmission rates by 41%. Yet primary care providers still treat it as a ‘nuisance’ rather than a clinical emergency. The fact that 37% of hypoglycemic events occur during tapering? That’s not negligence - it’s malpractice dressed in white coats.

I’m crying rn 😭 my mom was on prednisone for 3 months and they didn’t check her sugar until she passed out. She’s fine now but she’s on insulin and she doesn’t even have diabetes!! I hate the medical system. Why didn’t anyone tell us?!! 😭😭😭

My sister’s rheumatologist gave her a 2-week steroid pack and said ‘watch your sugar’ - then never followed up. She had ketones. Like, actual ketones. I had to drag her to the ER. If you’re on steroids, get a glucometer. Don’t wait for them to notice you’re dying. This isn’t hard. It’s not your fault. It’s their laziness.

While the article accurately outlines the pathophysiology and clinical management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, it is noteworthy that the term 'temporary diabetes' is potentially misleading. Although glucose levels typically normalize post-steroid discontinuation, the underlying metabolic stress may unmask latent prediabetes. Long-term follow-up is warranted, even in normoglycemic patients after cessation.

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me I have to check my blood sugar every day because some drug company decided to make inflammation medicine that turns your body into a sugar factory? 😂 Meanwhile, my dog gets more care than I do. Next time I’ll just take ibuprofen and hope I don’t die. 💅