Imagine you’re on two medications for high blood pressure and diabetes. Your doctor gives you a single pill that contains both drugs - a combo generic. It seems convenient. But how much are you really paying for that convenience? The answer might shock you.

In 2016, Medicare Part D spent $925 million more on brand-name combination drugs than it would have if patients had taken the same active ingredients as separate generic pills. That’s not a typo. Nearly a billion dollars wasted because of how these pills are priced - not because they’re better, but because the system lets manufacturers charge more.

Why Combo Pills Cost So Much

Fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) pack two or more drugs into one tablet. They’re marketed as easier to take, especially for people managing multiple conditions. But when one or both drugs are already available as cheap generics, the price jump doesn’t make sense.

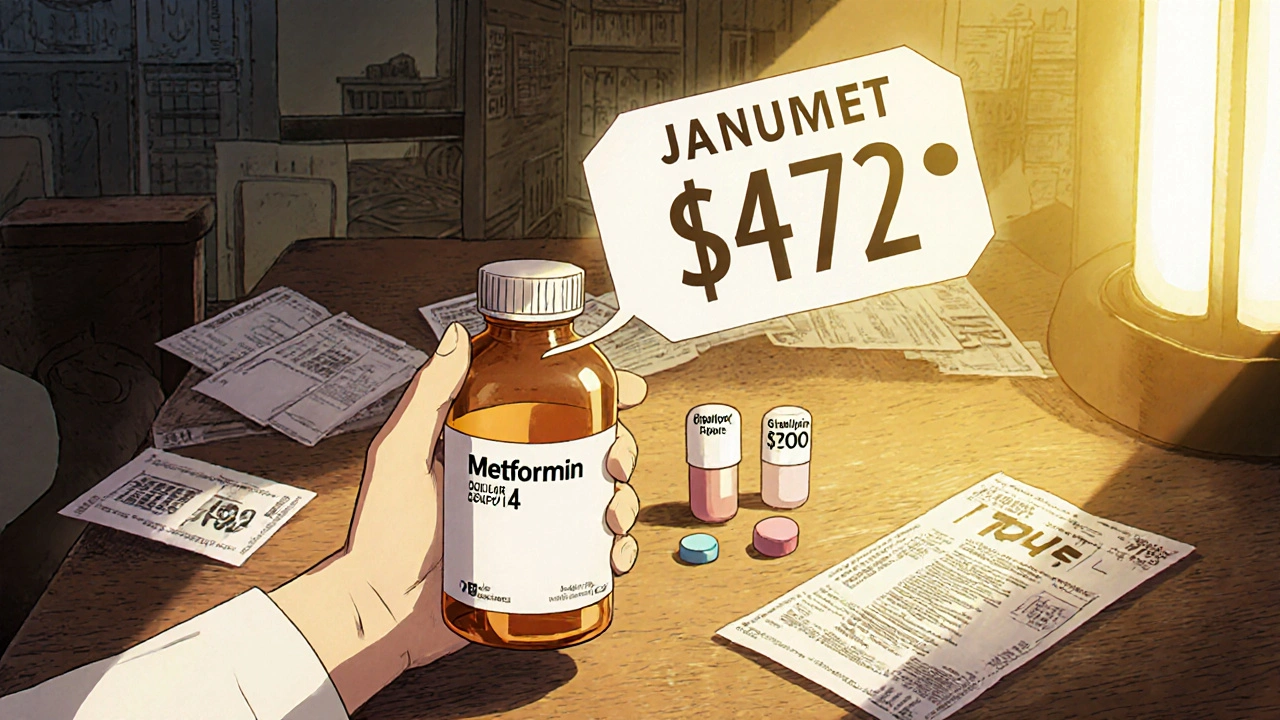

Take Janumet - a combo of sitagliptin and metformin. The branded version cost Medicare $472 for a 30-day supply in 2016. Meanwhile, generic metformin? As low as $4 at Walmart. Even if you added the cost of the branded sitagliptin (which was still under patent), you’d still pay less than half of what Janumet cost. That’s not innovation - it’s a pricing loophole.

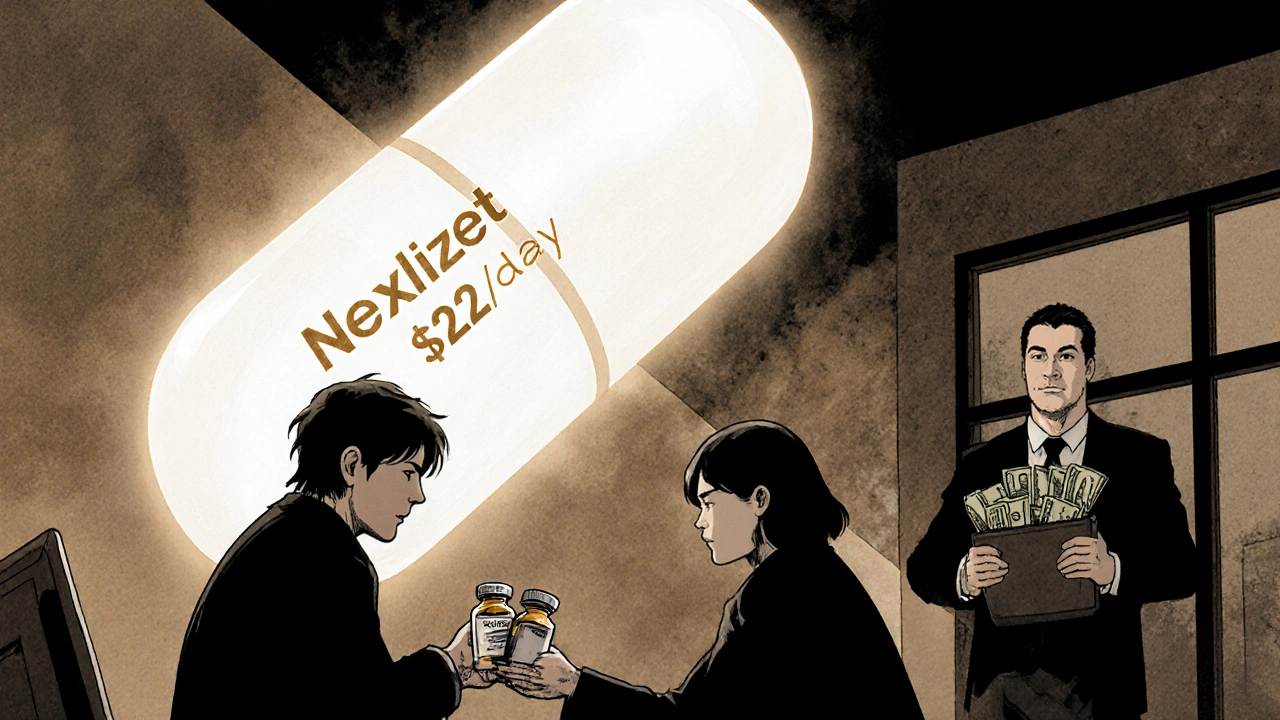

Manufacturers know this. When one drug in a combo loses patent protection, they pair it with a newer, still-patented drug. This trick - called “evergreening” - keeps prices high. Nexlizet, for example, combines ezetimibe (a generic for over a decade) with bempedoic acid (a new drug). Even though ezetimibe costs pennies, Nexlizet sells for $12 a day in the U.S. That’s over 300 times more than buying the generic alone.

The Math Doesn’t Add Up

Here’s the reality: 1 + 1 ≠ 1 when it comes to drug pricing.

IQVIA found that branded FDCs typically cost about 60% of what two separate branded drugs would cost. Sounds good, right? But when you compare them to generics, the math breaks down. For the 10 most expensive combo drugs between 2011 and 2016, Medicare could have saved $2.7 billion - a 73.5% reduction - if patients had taken the same ingredients as separate generics.

Let’s look at Kazano: a combo of alogliptin and metformin. The branded version cost $425 per month. Generic metformin? Less than $10. Even if you paid full price for alogliptin (say, $300), you’d still be saving $115 a month by buying them separately.

And here’s the kicker: 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled as generics. But combo drugs? They’re the exception. They make up just 2.1% of prescriptions, yet they account for 8.3% of Medicare Part D spending. That’s disproportionate. And it’s not because they’re more effective - it’s because they’re priced like luxury items.

Who Pays the Price?

You do. Even if you have insurance, you’re paying through higher premiums, deductibles, and co-pays. Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers all absorb these inflated costs - and then pass them on.

Patients on fixed incomes often skip doses or split pills to make combos last longer. Some skip one drug entirely because they can’t afford both. A 2020 study showed that patients taking multiple separate pills had lower adherence - but so did patients forced to choose between paying for a combo or buying groceries.

Meanwhile, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurers are trying to fight back. Over 60% of Medicare Part D plans now require prior authorization for high-cost combos. Some even create “carve-outs” - meaning they won’t cover the combo at all unless you prove you’ve tried the cheaper alternatives first.

When Combo Pills Actually Make Sense

This isn’t a blanket attack on combination drugs. Sometimes, they’re the right choice.

For patients with complex conditions - like HIV or heart failure - taking fewer pills improves adherence. Studies show adherence rates jump 15-25% with combos. That means fewer hospital visits, fewer complications, and lower long-term costs.

Entresto, a combo for heart failure, is one example. It combines sacubitril and valsartan. While valsartan is available as a cheap generic, sacubitril isn’t. Entresto works differently than older treatments. For some patients, it reduces hospitalizations by up to 20%. In those cases, the higher price can be justified.

The problem isn’t combos themselves. It’s when manufacturers slap a generic drug into a new combo and charge a premium - with no clinical benefit.

What You Can Do

If you’re on a combo drug, ask your pharmacist or doctor this:

- Are both drugs available as generics?

- What would it cost to buy them separately?

- Is there a clinical reason I need them combined?

Many doctors don’t know the exact cost difference. Pharmacists do. They can run a quick price check. You might be surprised.

For example, if you’re on a combo of metformin and a DPP-4 inhibitor (like sitagliptin or alogliptin), ask if you can switch to separate pills. The cost difference could be hundreds of dollars a month. And if you’re on Medicare, you can use the Medicare Drug Price Tool to compare prices at local pharmacies.

Some manufacturers offer patient assistance programs. Novartis, for example, offers Entresto for $10 a month to eligible Medicare patients. But that’s still 20 times more than buying generic valsartan and the brand sacubitril separately. It’s a band-aid, not a fix.

What’s Changing?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the most expensive drugs. That includes some combo products. The FDA is also pushing to speed up generic approvals under GDUFA III. More generics mean more pressure on combo prices.

Medicare’s Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has recommended that CMS create a payment system that reflects the real value of combos - not just their list price. That could mean paying less for combos when cheaper alternatives exist.

But change moves slowly. In the meantime, patients are left to navigate a system that rewards complexity over affordability.

The Bottom Line

Combo generics aren’t inherently bad. But when a drug company takes a $4 generic and pairs it with a $400 brand-name drug - and calls it a “new treatment” - that’s not progress. That’s profit-driven pricing.

Always ask: Is this combo saving me money, or just making someone else richer?

For most people, buying individual generic components is cheaper, just as effective, and gives you more control. If your doctor insists on the combo, demand a clear reason - not just convenience.

The system is rigged. But you don’t have to be.

14 Responses

theyre watchin us. every pill, every script, every barcode scanned. they know if you split your meds to save cash. the algorithm flags you as 'high risk' then ups your premiums. i saw it happen to my uncle. he asked for separate generics and suddenly his insurance 'lost' his claim. coincidence? nah. this is bigger than drugs. its control.

Irish people think they're clever for saving a few euros on pills while the rest of the world pays for their healthcare. You're not saving money-you're just delaying the inevitable hospitalization. The combo exists for a reason: compliance. Your 'generic hack' is a one-way ticket to a stroke or a diabetic coma. Stop pretending you're a pharmacist.

Oh, darling, let me unpack this for you like a poorly wrapped Christmas gift. The pharma-industrial complex doesn't sell medicine-it sells *narratives*. The combo pill? A beautifully curated illusion of convenience. A velvet rope around a $400 bottle of metformin wrapped in a lab coat. And we, the plebs, clap because we've been trained to equate 'one pill' with 'better.' The real tragedy? We're proud of our compliance while the CEOs buy yachts. I'm not mad. I'm just… disappointed. In us.

This is so important 💙 I was on a combo for years and didn't realize I could save $300/month by switching. My pharmacist helped me switch and I cried happy tears. You're not broken if you need help asking-just brave. Talk to your pharmacist today. You deserve to feel in control.

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been telling my patients this for years, but most don’t know how to ask. I always say: ‘If your meds cost more than your rent, something’s wrong.’ You’re not being difficult-you’re being smart. And you’re not alone.

Wow. Another ‘pharma is evil’ rant. Let me guess-you also think vaccines are microchips and the moon landing was faked? This is why America’s healthcare is broken. People think they know more than doctors because they read one article on Reddit. Grow up.

Oh please. You think you’re clever buying generics? You’re just a liability to the system. You think your ‘savings’ don’t get passed on to everyone else? Your ‘independence’ is a burden on ERs and Medicaid. You want cheap meds? Then stop being a selfish, entitled brat who thinks your health is a bargain bin item.

They’re putting tracking chips in the pills. I read it on a forum. The combo pills are worse because they can monitor your blood pressure remotely. They want to know when you skip a dose so they can raise your rates. I don’t take combos anymore. I take the pills separate and hide them in my cat’s food. They can’t track the cat.

From a pharmacoeconomic standpoint, the cost-discrepancy is statistically significant (p < 0.001). The marginal utility of fixed-dose combinations diminishes exponentially when both agents are off-patent. The PBM rebate structure incentivizes formulary placement of high-list-price combos, creating perverse incentives. This is textbook market failure. The FDA should enforce unit-cost caps for FDCs containing ≥1 generic component.

I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years. I’ve watched people skip doses because they couldn’t afford the combo. I’ve seen people cry in the aisle because they had to choose between insulin and rent. This isn’t about politics. It’s about dignity. You don’t need to be a genius to know that $4 metformin + $15 sitagliptin is better than $472 Janumet. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way. But you? You can still choose to fight back. Ask the questions. Demand the truth. Your life is worth more than a corporate spreadsheet.

Man, I used to take that Janumet combo. Thought I was being smart. Then my buddy showed me the math. I switched to separate pills, saved $280 a month, and bought a new pair of shoes. No joke. My feet hurt. The combo didn’t make me feel better. Just poorer. If you’re on one of these, just ask your doc. Worst they can say is no. But you might just get your life back.

Adherence rates are a red herring. You're romanticizing non-compliance as ‘empowerment.’ The reality? Patients who split pills have higher rates of adverse events. The combo reduces pill burden, which reduces cognitive load, which reduces errors. Your ‘savings’ are a myth-you’re just gambling with your health. And now you want to make it everyone else’s problem?

THEY KNOW. THEY KNOW YOU’RE DOING THIS 😭 I saw a guy on TikTok get audited because he bought metformin at Walmart. His insurance flagged him as ‘fraudulent.’ They’re coming for us. 💀 I’m switching back to the combo. I don’t want to be labeled. I just want to live. 😔

Stop lying to yourself. You think you’re saving money? You’re just delaying the inevitable hospital bill. The combo is cheaper in the long run. Your pride is costing you more than the pill.